Forage Establishment

Forage establishment is a long-term investment requiring careful planning, preparation, species selection and management to ensure success. Proper establishment of the forage stand plays a vital role in stand productivity and longevity. Begin planning at least 18 months prior to seeding forages to effectively control weeds and manage fertility.

On this page:

Key PointsSelecting the Right Forage

Fertility

Successful Seeding

Maintenance of Forage Stand

|

Selecting the Right Forage

Land managers must carefully consider the long-term needs and goals for the forage stand and how it will function within their operation to select the appropriate species. Planning is key. Start at least 18 months prior to seeding to allow time for proper species selection, weed control, seedbed preparation, soil tests and pre-seeding fertilization. Perennial stands will usually be in production for many years, so treat it like a long-term investment. Environmental factors, intended use and stand life will impact forage species selection. Consider the land type, forage needs and utilization for the stand.

Consider the following:

- What is the intended use and when is the preferred season of use? Will it be pasture or hay? Will it be used for spring grazing, summer hay, fall or winter grazing?

- What is the management system? Will it be rotational, continuous, mob grazing?

- How long will the stand be in production?

- What are the specific environmental conditions, soil type, annual precipitation, winter temperatures, problem areas such as flooding, run-off, alkaline or saline areas?

- What are the specific herd needs?

- Is a single species or a binary mixture (two species) better suited to the requirements and environment? Can native species be used?

Intended Use of the Forage Stand

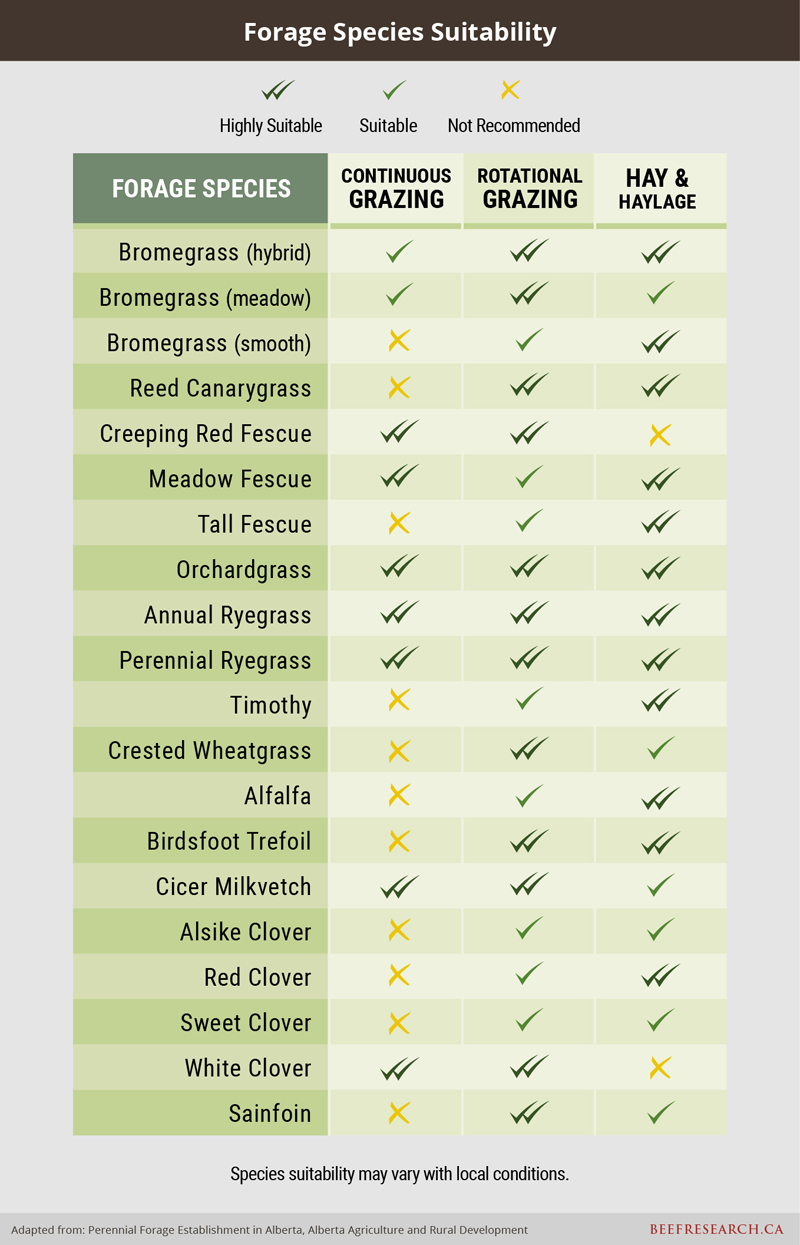

Forages vary in their suitability for hay and pasture, and for different management systems. Consider the use, frequency and type of harvest when determining stand composition. Native species, crested wheatgrass and low growing forages such as white or kura clover are not well suited to mechanical harvesting and are better utilized as part of a grazing system. Alfalfa, on the other hand, does not tolerate frequent grazing without stand loss, and unless managed carefully may be more suitable for haying. Other forages suitable for haying include smooth and hybrid brome grasses, rye grasses and timothy. How a stand will be managed will help determine species selection as certain varieties perform better under different conditions.

Timing of Use

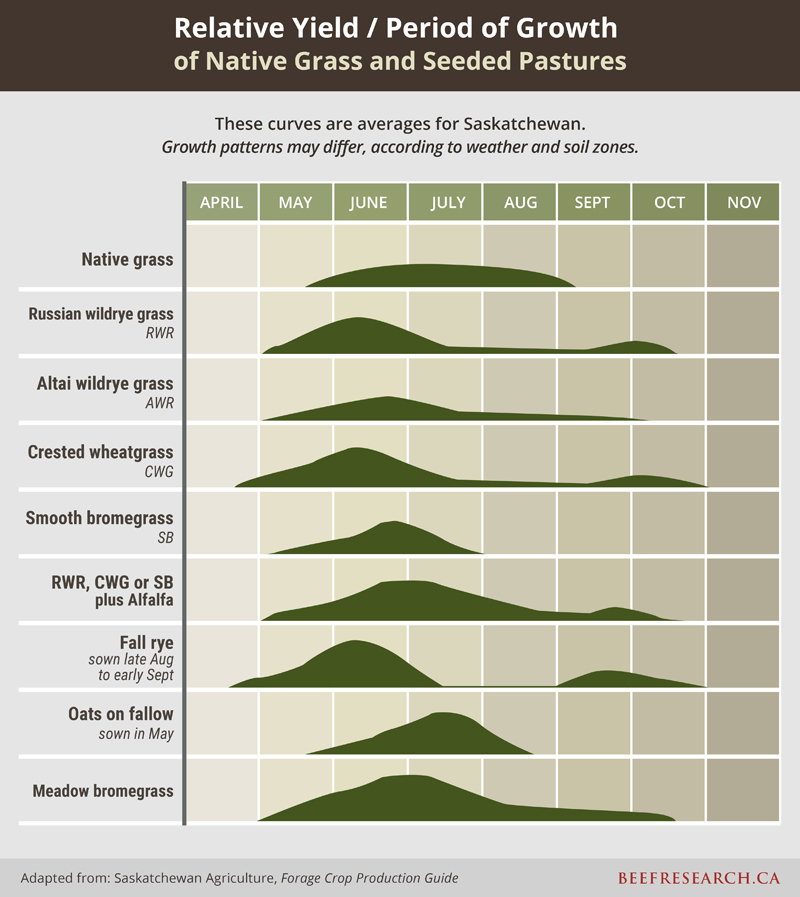

Selection of the forage species will depend largely on when and how a producer wants to utilize the stand. Forage species vary in growth patterns, yield, nutrition levels and response to grazing or haying. Crested wheatgrass is an early season grass which could be suited to early turn-out at calving, or for pairs following calving. Alfalfa’s growth pattern fits well with rotational grazing, using rapid, even grazing, followed by a long rest period. Although it tolerates close grazing or haying, it does not tolerate continuous grazing. As with all species, native plants should be grazed during their optimal growth period and when growing conditions are favourable. Rest and recovery are the most important aspects when determining timing of use.

Single Species or Mixture?

To determine whether single species or a mixture provides the best option for the new forage stand, producers consider many factors. Single species work well for single end uses, while mixtures, such as grass-legume blends can provide more options, such as harvesting for hay or silage as well as grazing. To increase protein levels and digestibility of forage, producers often consider a forage mixture that contains a legume such as alfalfa. Grass species that grow well when planted with alfalfa include: meadow bromegrass, timothy, crested wheatgrass, orchard grass and tall fescue. Mixtures containing 30-40% legume can usually produce enough nitrogen for their needs, reducing the need for regular applications of nitrogen fertilizer. Grass-alfalfa mixtures can reduce risk of bloat, while increasing the length of the grazing season.

Research conducted by Dr. Yousef Papadopoulos at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Experimental Farm in Nappan, Nova Scotia examined four different pasture blends. The combinations consisted of timothy, meadow fescue, reed canarygrass, Kentucky bluegrass, tall fescue, meadow brome and orchard grass with either birdsfoot trefoil or alfalfa. Yields were higher with the alfalfa blends, yet animal performance was better on the blends containing trefoil. Over the five years of the trial, both legumes declined in the stands, affecting both yield and performance. Results are highly variable and forage mixtures may exhibit different results across the many regions of Canada.

| Longevity and yield of a forage stand begins with choosing a variety adapted to the intended use, environment and field conditions. High quality Certified seed is recommended as it provides legal guarantees for varietal purity, germination, and freedom from impurities such as weed seeds. |

In the following webinar, Dr. Surya Acharya discusses new forage varieties and research at Agriculture Agri-Food Canada Lethbridge Research and Development Centre.

Tame vs. Native Grasses

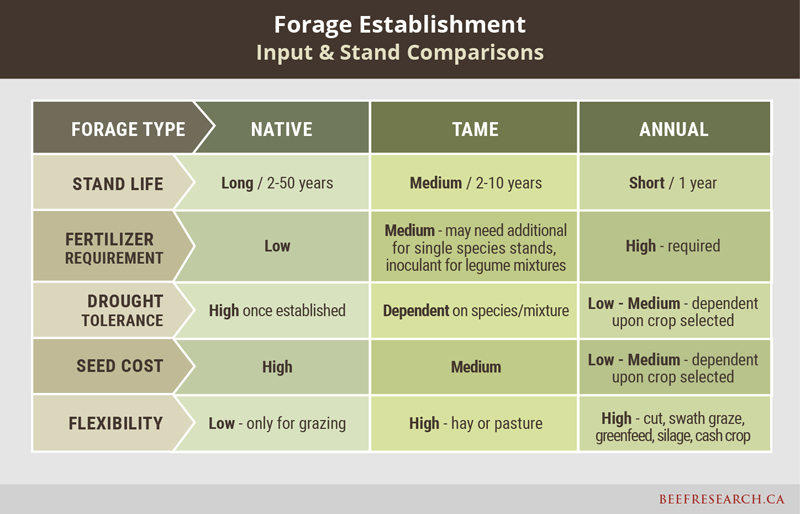

While tame forage species are often the first choice for producers establishing a new stand due to reduced cost, seed availability and faster establishment, native species can outperform in certain growth limiting environments over the long term once well established. Under optimum conditions, tame forages can have higher yields, and offer flexibility in terms of cutting for hay, or swath grazing, while native rangelands and pastures on marginal lands exhibit drought tolerance and resilience. Where possible, preserve and maintain native species; choose lands for new forage establishment that would benefit from having perennial cover, such as areas prone to excess moisture, or run-off and erosion. Producers on mixed operations must consider the opportunity cost of higher valued land when it is seeded to forages. Less productive land is often a better fit for establishing or re-establishing native stands. The table below illustrates yield and period of growth of native grasses in Saskatchewan, relative to several common tame grasses and annuals.

Seeding Annual Crops as Forage

Seeding an annual, such as barley, oats, triticale or ryegrass as a forage source can provide additional feed, tonnage or grazing flexibility. Annuals can provide rest and recovery of perennial pastures from grazing, as well as supplement feed during drought, or late seeding options when excessive spring moisture prevents normal seeding of annuals. Fall seeded winter cereals can be grazed in mid-May, reducing pressure on pasture. Annuals can also extend the grazing season and provide excellent quality feed if grazed or cut for greenfeed hay, swath grazing or silage.

The inclusion of a field or forage pea can boost protein levels. Intercropping involves planting a spring cereal with a winter annual, allowing the flexibility to harvest spring cereal for silage, and leave the winter cereal below for mid to late season grazing. Another use of annuals is as a cover crop. They can provide a quick-growing source of forage and can be grazed in the season they are planted. There is much interest in cover crops/poly crops by both livestock producers and farmers as a feed source and a means to improve soil properties. Research is ongoing in this area.

The following table summarizes key characteristics and comparisons of native, tame, and annual forages.

Companion Crops

Companion or nurse crops can be useful in suppressing weeds and reducing erosion, can provide protection from the elements for forage stand establishment, and provide extra feed during the first year when cut early as silage or greenfeed. In certain areas of Canada, such as the Maritimes, forage crops have traditionally been under seeded with a cereal companion or nurse crop. Forages such as red clover, timothy and rye grasses seem to establish better in a companion system than alfalfa and most other grasses. A companion crop will always compete with the forage crop for nutrients, light, and moisture. This can reduce the survival rate and subsequent yield of the forage stand. Select the companion crop species to minimize competition with the forage species selected for the stand. Companion crops should be seeded at half the normal rate and harvested early to reduce competition to the main forage stand after it has established.

In drier regions, success with companion crops is limited. Research at three sites in Saskatchewan over a three-year period examined the use of annual crops such as field pea, canola and ryegrass as companion crops for establishment of forages. The economic returns were worse with a companion crop at two locations, Swift Current and Saskatoon, but slightly better at Nipawin1. This research demonstrated that the feasibility of companion crops for establishment of short-lived perennial forages in Saskatchewan depends on soil zone, with the more humid areas being the best suited to the use of companion crops.

Fertility

After conducting a soil test, determine the nutrient requirements for the selected forage stands. Create a pre-seeding fertilization plan that enhances germination and establishment by correcting possible nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and sulphur deficiencies.The fertility requirements will differ based upon the forage species as well as the soil composition and conditions. Calculate the costs and time to amend soil or correct deficiencies. In the event that the soil tests reveal significant deficiencies that would be too costly or prohibitive to correct, alternative species selection may be required. Local conditions will vary greatly. Contacting a Professional Agrologist to conduct the soil tests and make recommendations based upon the results will increase success rate and ensure that the proper fertilizer is applied. Consider the 4R’s - use the right source, at the right rate, the right time, and the right place.

| Forage seed and fertilizers can be costly; plan for success by having a Professional Agrologist conduct soil tests and create a fertilization plan for the forage stand. |

Nutrients - Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) potassium (K) and sulphur (S) are key nutrients to test for and supplement if necessary, prior to establishing a new forage stand. Producers often cite declining productivity within their forage stands as the reason for termination and re-establishment of a stand. Ensuring that the nutrient levels are sufficient for the species selected will assist with stand establishment and forage yields. Macronutrients calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) are required for alfalfa growth but are usually available in adequate amounts in Western Canada2. Micronutrients such as boron, copper, manganese or zinc, may also be required, but should only be applied at the recommendation of an agrologist based on soil tests.

Nitrogen

Nitrogen (N) assists with plant growth and yield. Ensure that nitrogen levels are adequate prior to seeding to provide enough nutrition for the seedlings to have healthy emergence and establishment. The forage species selected will determine the nitrogen requirements based on soil tests. Pure stands of perennial grasses are more prone to nitrogen deficiency than mixtures that contain legumes such as alfalfa, which can fix atmospheric nitrogen when properly inoculated. The addition of legumes can boost productivity and value of the stand, as costs and demand for nitrogen are reduced. Application of nitrogen to an alfalfa stand will reduce the proportion of alfalfa within the stand over time, as it reduces nodulation of the legume and decreases their ability to fix atmospheric N. Pure grass stands may benefit from nitrogen applications for optimum production during the life of the stand, provided adequate moisture exists to achieve a positive response. Variables such as fertilizer and hay prices impact the benefit received from fertilization.

Applying the total nitrogen required at one time can increase risk of loss through volatilization or run-off. Splitting the application of nitrogen can reduce losses and diminish damage to seedlings, which can be injured by high amounts of N.

Sources of nitrogen can include urea-ammonium-nitrate (UAN), urea, and anhydrous ammonia. Urea can be broadcast, (spread on top of the ground) banded (injected or drilled into the ground), or incorporated at seeding with certain seeding equipment.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus (P) plays a vital role in root development and is important for establishment of a new stand. Phosphorus is immobile in soil, meaning that the fertilizer needs to be placed 2.5 centimetres below and 2.5 centimetres to the side of the seed. For this reason, broadcasting phosphorus during the year of establishment is not recommended. Banding is preferred. If long term planning has occurred and soil tests indicated low P levels, broadcasting for one or two seasons prior to establishment can be effective, as the P becomes incorporated into the soil over time and will then be available at seeding. Many soils across Canada have phosphorus deficiencies. If seeding legumes such as alfalfa, the soil pH is very important, with a target of 6.5 - 7.0. At higher and lower values, phosphorus availability is reduced, compromising establishment and healthy root development.

Potassium

Potassium (K) is responsible for root development and yield, stand persistence, disease resistance and winter survival. Potassium can be limiting on lightly textured grey soils, and deficient in sandy, intensively cropped soils. Banding or broadcasting potassium fertilizer are both effective ways to apply potassium. Grasses do not require as much potassium as mixtures containing alfalfa. When forages are cut as hay, significant amounts of potassium are removed from the soil. Sandy loam soils in particular demonstrate both a yield and protein response to K application. Ensure adequate levels prior to planting, and repeat soil tests annually to ensure optimal levels are maintained.

Sulphur

Sulphur (S) is required for nitrogen fixation by legumes and for protein metabolism. If incorporating alfalfa into a forage blend, sulphur is an important nutrient to test and manage for since it directly impacts yield and protein levels. Deficiencies are common across Canada on well-drained sandy soils, grey wooded soils and soils with low organic matter3. Sulphur can be more difficult to test for prior to seeding a new forage stand, as the most accurate measurement of sulphur content is determined through plant tissue testing. Alfalfa requires and removes more sulphur than pure grass stands, so it should be considered for mixed blends containing alfalfa. Low pH levels also make sulphur unavailable to the plant. Visual symptoms of a sulphur deficiency will include stunted plants with reduced internode growth and purple to yellow leaves.

Certain conditions can limit key nutrients and micronutrients available to the forage, impacting yield and health. Soil tests that identify these conditions can alert producers to potential issues. The following table identifies limiting conditions.

Successful Seeding

Moisture is the most important factor in successful germination and establishment of forage crops, so proper timing and weed control are vital to conserve moisture for the seedlings. In most areas, early spring seeding produces the best results because adequate moisture is usually available, and temperatures are conducive for germination. In areas with less precipitation, direct seeding into stubble is an effective way to preserve moisture to enhance germination and to provide some shelter for emerging seedlings from harsh, drying winds. Areas with excessive moisture can utilize frost seeding or later season planting to avoid soil compaction.

If conditions are not conducive to spring seeding, summer seeding and fall/winter dormant seeding provide alternative timing options. Frost seeding usually occurs in early spring, just prior to frost coming out of the ground. Some areas in Manitoba and the Maritimes are seeded using broadcast or frost seeding to manage for anticipated excessive moisture conditions that can force producers to seed later than desired. Late season seeding carries a risk that the seedlings may not build up sufficient nutrient reserves to over-winter successfully. If using dormant or frost seeding techniques, increase seeding rates by 25% to offset seed and seedling mortality. Fall dormant seeding (seeding in late fall before the ground freezes), works well if direct seeded into stubble at a soil temperature below 2°C which prevents germination until spring.

Weed control in prior crops can impact forage establishment success. Consider crop rotations and weed control that will reduce weed seed bank. Control weeds such as Canada thistle, quack grass, and dandelion prior to planting, as they compete for moisture and nutrients and can be difficult to control after seeding. If using manure as a nutrient source, be aware that it may also introduce viable weed seeds. Ideally, manure would be applied the prior year to allow time for weed seed germination and control prior to planting the forage stand. Ensure that any herbicides applied in recent years will not have a residual effect that can impact germination of forage seedlings. Some native grass species are sensitive to residues from Group 2, 3, 5 and 8 herbicides which include Edge, Avadex, and Odyssey. Lontrel and 2,4-D can reduce seedling survival and stand establishment of legumes4.

If re-seeding alfalfa into an existing or recently terminated alfalfa stand, autotoxicity must be managed for. Alfalfa is unique because it produces a toxin, medicarpin, that permits the plant to manage its own stand densities. This becomes a problem when seeding into an existing stand, or one that has been reduced by winter-kill or flooding. Wait at least 12 months before seeding an alfalfa forage mixture back into a field that previously grew alfalfa to avoid reduced plant vigour and lower yields due to alfalfa autotoxicity.

Forage seeds are often small and light; an ideal seedbed should be smooth, well-packed, moist and weed free to provide critical seed-to-soil contact for successful germination. Excess straw or residue on the field from prior crops can impede seed-to-soil contact and negatively impact germination. When planning 18-24 months in advance of seeding the forage crop, harvest methods in the prior years can include baling extra straw, harrowing or ensuring that the straw is well chopped and spread coming out of the combine.

Seeding equipment that provides proper depth and seed placement generally yields better results than broadcast methods; proper depth is key.

Recommended Seeding Depths

Seed 1/4” - 3/4” (0.65 - 1.25 cm) deep in fine textured, clay soils, and if forage seeds are small (i.e. timothy)

Seed 1/2” - 1” (1.25 - 2.5 cm) deep in loam

Seed 3/4” - 1 1/2” (2 - 3.75 cm) in sandy soils

If a broadcast method is used, roll or harrow pack afterwards to improve seed-to-soil contact.

Seeding rates will depend on the type of forage, soil type, moisture availability, the desired number of plants per square foot or square metre, and the type of seeder used. Plant populations and seeding rates should increase with increasing soil quality and available moisture. Target Pure Live Seed (PLS) densities are:

- 18-20 seeds/ft2 (15-16 seeds/m2) PLS in Brown soil zone

- 20-25 seeds/ft2 (16-20 seeds/m2)) PLS in Dark Brown soil zone

- 25-30 seeds/ft2 (20-24 seeds/ m2) PLS in the Black/Grey Wooded soil zone

- 30-40 seeds/ft2 (24-32 seeds/ m2) PLS under irrigation

Row spacing in forage stands is generally recommended at 12-14 inches (30-35cm) and 6 inches (15cm) under irrigation.

To calculate the seeding rate in pounds per acre (or kg/ha) multiple the target seed density by 43,560 square feet in an acre (or by 1000 m2/ha) and divide the total by the number of seeds in a pound (or kg) of the species.

For example, using the Dark Brown soil zone with certified seed of 79% germination and 98% purity, the Pure Live Seed would be:

Pure Live Seed = Germination% X Purity %

= (0.79 X 0.98)

= 0.77

Seeding Rate (lbs/ac) = seeds/ft2 X ft2/acre / PLS

seeds/lb

= 22 seeds/ft2 X 43,560 ft2/acre / 0.77

200,000 seeds/lb

= 4.79 lbs/acre / 0.77

= 6.2 lbs/ac

The factsheet Successful Forage Crop Establishment, reprinted with permission from the Saskatchewan Forage Council, provides more detail on seeding calculations.

| Legumes such as alfalfa, sainfoin, vetches, and trefoil need to be properly inoculated before seeding to enable them to fix nitrogen from the air into the soil. |

Producers seeding forage stands under irrigation, or in zones with adequate moisture have more flexibility in seeding methods and equipment. In high moisture areas, broadcasting seed may be the best option. Harrow/packing and timely rain or adequate moisture will determine success with broadcast methods. If using hoe drills, double disc press drills or air seeders, be aware of common issues with each. For example, forage seed can be small and fluffy, causing bridging in seeders without an agitator. Press drills pack the seed well for soil-to-seed contact, but discs sometimes cannot penetrate straw on the surface, while hoe drills can bunch up any excess straw or crop residue in front of the shanks and plug, creating missed runs. Air seeders and drills can seed a large area, have good trash clearance and depth control for small seeds. Seed is packed well for good contact and germination. Because the forage seed is so light, the fan speed must be kept lower to avoid blowing the seed out of the furrow.

Some producers report that their cattle have consumed the seed pods of legumes such as cicer milkvetch and sainfoin, and distributed them across pastures in the manure, where the seeds then germinated. While this method is unpredictable, it may be a way to slowly increase legumes in a stand.

Economics

The decision to establish a new forage stand requires research into species selection, timing of use, plus many other factors described above. The economics of the decision should be analyzed prior to establishment.

Costs include:

- seed

- fertilizer and crop nutrition inputs

- weed control inputs, herbicide

- equipment rental, custom seeding

- maintenance costs over life of stand (i.e. weed control, fertilization, rejuvenation)

Compare and contrast those costs with:

- days of grazing and estimated animal performance or custom pasture rental income

- market cost and estimated yield if haying and selling forage as cash crop

Maintenance of Forage Stand

After successfully seeding and establishing the new forage stand, consider the following best management practices to ensure ongoing success and production of the new stand. In addition to designing a grazing management strategy that best utilizes the new stand, consider weed control and nutritional requirements to maximize your investment.

Be alert to any insect or disease pressure that might compromise establishment and stand longevity. Grasshoppers can be problematic in dry areas of the Prairies, while the Maritimes may have European Skipper infestations on timothy, perennial ryegrass and meadow fescue. Armyworms and potato leafhoppers are often seen affecting forages in Ontario and Quebec.

In this picture, armyworms ate all the pasture grasses, leaving only broadleaf weeds behind.

Manage the new stand carefully, with no grazing in the first year. Second year grazing potential will depend upon forage species chosen and level of establishment success. Utilize new stands with a “take half, leave half” mentality. Re-seed bare spots and monitor for weeds and pests5.

In the establishment year:

- grazing is not recommended

In the second year after establishment:

- grazing will depend upon forage species chosen and level of establishment success. The ‘take half, leave half’ concept helps to ensure root development is not compromised by removing too much plant material too early

- assess and control for weeds as necessary

- fill any bare spots that did not establish by broadcasting new seed on those areas

- soil or tissue test to ensure adequate soil fertility, top dress with fertilizer if necessary

- monitor for insect pressure that could reduce the stand while it is still establishing

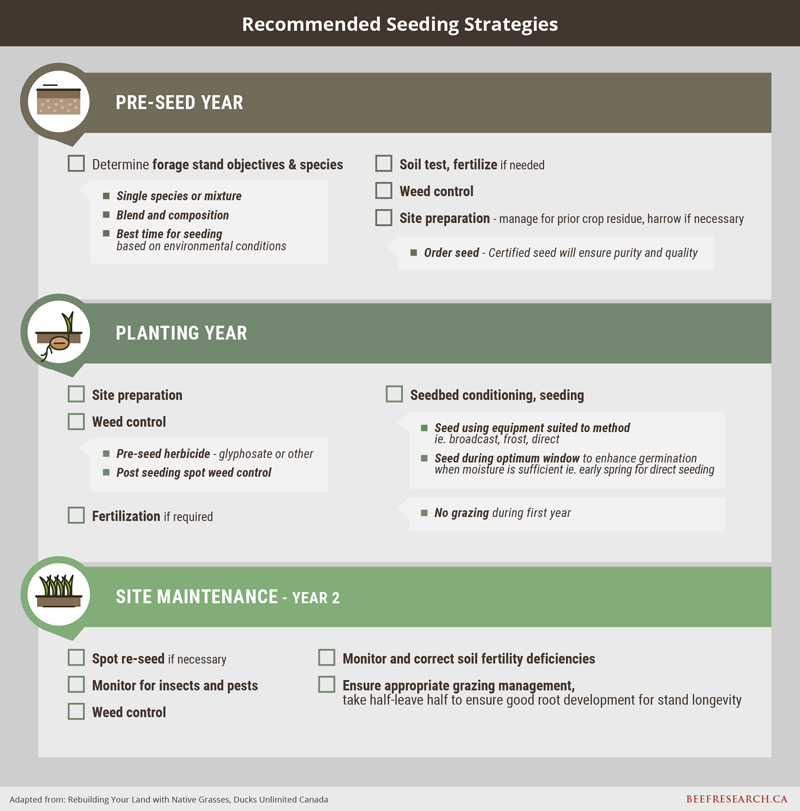

The following table, adapted from Rebuilding your land with Native Grasses, provides an overview of the process for successful forage establishment5.

Conclusion

The long-term nature of forage crop stands requires careful planning to ensure proper species selection for the intended use, as well as successful establishment and maintenance. While native forage stands can be more costly and slow to establish, they generally require less long-term management in terms of fertility. Several research studies indicate a net benefit to including a legume in a forage stand, both in terms of feed value and overall economics of forage production. Grazing management strategies will play a role in determining forage species selected and the ongoing success and productivity of the stand. Regional variation in soil types and climatic conditions necessitates soil testing to determine any necessary soil amendments, as well as plays a significant role in the determination of the best single, binary, or complex mixture to plant. Ensuring a clean field through weed control and enabling good soil-to-seed contact will enhance germination and establishment. Managing the new stand for grazing pressure, insects and weeds will be especially important in the first couple of years to ensure a productive and long-lived stand.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us.

This topic was last revised on November 19, 2019 at 8:11 AM.

View Web Page

View Web Page View PDF

View PDF