Specified Risk Material (SRM) Disposal

The term specified risk material (SRM) refers to parts of cattle that could potentially contain the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) agent (prion) in an infected animal. The transferrable BSE agent in BSE-infected cattle has been found to concentrate in specific tissues that are part of the central nervous and lymphatic systems, such as the skull, brain, spinal cord, nerves, and tonsils.

On this page:

- What is specified risk material?

- Managing the risk of BSE through safe handling of SRM

- What are the CFIA’s SRM regulations that producers need to know?

- Safe disposal of SRM

- What are the issues and research going forward?

What is specified risk material?

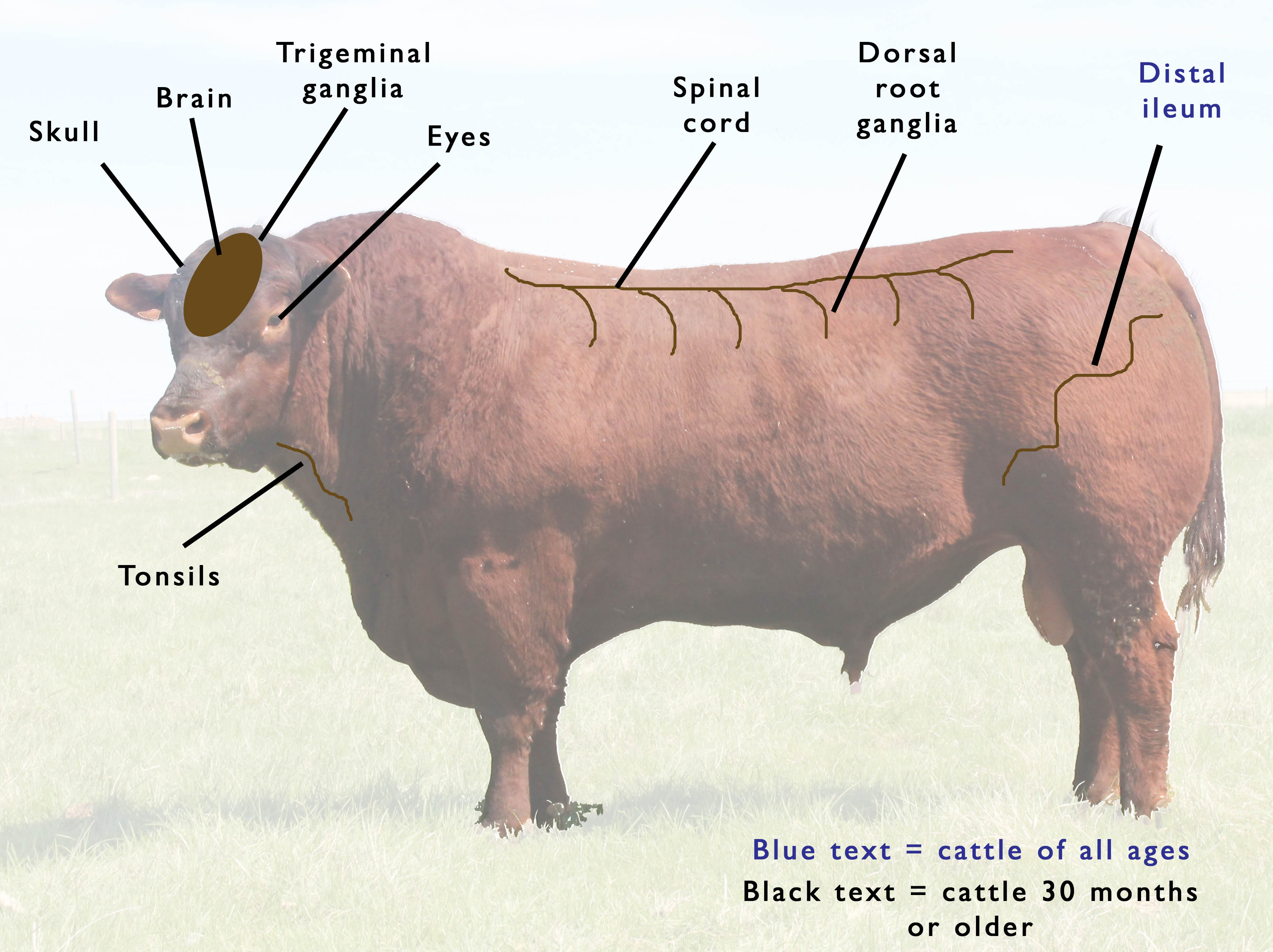

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) defines SRM as: “The skull, brain, trigeminal ganglia (nerves attached to the brain), eyes, tonsils, spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia (nerves attached to the spinal cord) of cattle aged 30 months or older; and the distal ileum (portion of the small intestine) of cattle of all ages.”

The CFIA indicates that the carcasses of condemned cattle and cattle deadstock (of any age) that contain SRM must be treated as SRM. Even inedible material mixed with SRM, such as floor waste or recovered solids from waste water, must also be treated as SRM. More information on the CFIA definition of SRM can be found online here.

BSE is not a ‘contagious disease’. It is transmitted through the consumption of animal by-products or feed contaminated with BSE prions. Since the BSE prions have not been shown to accumulate in muscle or milk, animal products that do not contain SRM do not transmit the disease.

Safely managing BSE – and the cattle tissues designated as SRM where BSE-causing prions concentrate – is an important goal for consumers, cattle producers and the Canadian beef industry.

Managing the risk of BSE through safe handling of SRM

|

[prion (prē·ŏn) n.] A protein found in the brains of mammals that when misfolded causes infectious diseases of the nervous system such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle and chronic wasting disease in deer, elk and moose. |

Canada is one of the largest exporters of red meat and livestock in the world. As of 2017, our country produces approximately 1.3 million tonnes of beef annually and exports around 45% of our beef and cattle production each year to 56 countries worldwide.

In 1993, the first case of BSE, or so-called ‘mad cow’ disease, was discovered in Canada in a beef cow that had been imported from the United Kingdom (UK) in the 1980s. The animal was destroyed and an investigation was launched to find and eradicate all of the cattle in Canada that had been imported from the UK.

Canada's first case of BSE in a domestic animal was found in May 2003. It is believed that some of the 182 UK cattle imported by Canada and the United States between 1982-1990 that had been slaughtered and rendered were responsible for the BSE that was detected in a Canadian animal in 2003. Due to the long incubation period of BSE, the UK cattle could have been infected with BSE despite appearing healthy when entering the country. The 2003 discovery closed international trade borders to Canadian beef and cattle, and cattle prices plunged overnight. The BSE crisis that began in 2003 is estimated to have cost beef producers and the Canadian economy atleast 5 billion dollars.

Shortly after the first outbreak of BSE in Canada, and in the years following, the Government of Canada took several steps to protect consumers, the industry and the livestock.

- in 1997, acting on the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO), the Government of Canada banned the feeding of ruminant proteins from cattle feed to limit the spread of BSE among cattle

- in 2003, with the detection of BSE in the first domestic cow, further legislation required the removal of any SRM cattle tissues capable of transmitting BSE from all cattle slaughtered for human consumption

- in 2007, to provide enhanced animal health protection and help eliminate BSE from Canada, the Enhanced Feed Ban (EFB) banned SRM from all animal feeds, pet foods and fertilizers

- in 2012, the CFIA announced a review of the enhanced feed ban

-

today, a permit system is enforced by the CFIA across the country for the collection, transport, treatment and disposal of SRM

As the Canadian cattle industry moves forward, legislation for the management of BSE is in place to uphold public health and safety, plus meet criteria for maintaining Canada’s standing within the OIE ranking.

Of the 54 member countries the OIE tracks for BSE risk status, Canada is among only six countries or zones with a ‘controlled risk’ status (as of July 2018). The other 48 countries are ranked ‘negligible risk’. Although countries with both ‘negligible risk’ and ‘controlled risk’ status must identify, track and prevent known BSE-infected animals from entering food and feed chains or export trade, much more rigid criteria must be met for those countries identified as ‘controlled risk’.

Countries with ‘controlled risk’ status can apply for a ‘negligible risk’ status 11 years after the date of birth for the most recently born bovine to test positive for BSE, provided the country’s ruminant feed ban and surveillance systems meet OIE standards.

In the meantime, countries importing beef can choose from many markets with a status of ‘negligible risk’. Although Canada’s current BSE risk status impacts relationships with our trading partners and the demand for Canadian beef, the good news is that Canada’s BSE risk is extremely low. This is indicated by the small number of cases detected from the improved surveillance systems now in place. To learn about the current surveillance system, visit the CFIA website.

The safety of Canadian beef products is ensured by this surveillance system, the legislated ban of SRM in feed and fertilizer and the exclusion of SRM from the human food supply at the time of slaughter. If a new BSE case is detected, it is an indication that Canada’s detection system is working.

What are the CFIA’s SRM regulations that producers need to know?

A permit is required for transporting and disposing of SRM so that the CFIA can track and maintain control over SRM, and ensure SRM doesn’t enter the food system, livestock feed, pet food or fertilizer.

The CFIA’s regulations for the cattle industry affect transporters, auction markets, abattoirs, processors and producers. When it comes to the management of SRM by cattle producers on the farm, there are two main areas that producers need to know about:

- on-farm disposal

- transportation of SRM

On-farm disposal of deadstock or SRM

Cattle deadstock and/or raw SRM that remain on-farm are not subject to CFIA requirements, if all material (including composted cattle remains) stays on the farm.

Different provinces may have different legal requirements around which disposal methods are acceptable, both on-farm as well as for small abattoirs. Be sure to check with your provincial authorities, or your provincial beef producer organization, for the most current information.

Moving SRM

A permit issued by the CFIA is required to transport SRM in any form (including cattle deadstock), or transport or receive edible carcasses containing SRM for cutting or processing.

For inedible carcasses, a special marking dye approved by the CFIA must be used on inedible SRM material, and a visible stripe must be applied down the backs of any carcasses containing SRM.

For edible carcasses, the following applies:

- carcasses of cattle older than 30 months of age must be stained with a meat dye to mark the spinal cord or vertebral column

- eviscerated carcasses from cattle younger than 30 months of age that no longer contain the intestine are considered free of SRM and so are not subject to CFIA transportation requirements

Records for all SRM and cattle carcass movement must be kept for a minimum of 10 years.

For complete information on Enhanced Animal Health Protection from BSE, visit this section of the CFIA website.

Safe disposal of SRM

Since the detection of BSE in Canada, disposal through traditional channels such as rendering has become more expensive for cattle producers, and in some cases, less available.

There are several ways Canadian producers can dispose of SRM. While there are many disposal methods, some work better than others at destroying or containing the BSE-causing prions that concentrate in SRM.

SRM can be disposed of in the following ways:

|

Different provinces may have different legal requirements around which disposal methods are acceptable, both on-farm as well as for small abattoirs. Be sure to check with your provincial authorities, or your provincial beef producer organization. |

- rendering

- natural exposure

- incineration

- burial on-farm or in an authorized landfill

- on-farm animal mortality collection services

- on-farm composting

Visit our page on “Disposal of Cattle Mortalities” for more detailed information on each disposal method, along with a pro and con assessment for each.

Rendering

Rendering is a process that converts animal remains into products that are useful in other ways. For example, animal fatty tissues can be converted into purified fats like tallow. Rendering, if available in your area, is as easy as calling (and paying) for pick up. Pick up times must be timely, as carcasses must be in good condition to be accepted for rendering. Minimum weights may apply and distance to the plant will determine the cost for producers. Deadstock pick up is not available everywhere.

- in a post-BSE environment, only hides and tallow products can be marketed; meat and bone meal cannot

- complete removal of the deadstock from the farm provides good on-farm disease control

- biosecurity measures should be followed, and pick up locations should be separate from healthy livestock

Natural exposure

Although many provinces allow carcasses to be disposed of by scavengers, due to the high possibility of the spread of disease, this method is not recommended, and may not be legal in all provinces. Each province has regulations for natural disposal, so check with your provincial agriculture authorities for these regulations.

If BSE or other diseases (such as anthrax) are suspected, this form of disposal should never be used, as natural disposal does not completely destroy the prions that cause BSE, and some other viral or bacterial organisms may also survive this disposal method. If predation is an issue in your area, natural disposal is highly discouraged as it teaches predators there is an easy food source in the vicinity and consumption of carrion can increase the risk of disease spread.

Incineration

Incineration involves burning the whole carcasses (including bones) at a high temperature (higher than 850 degrees Celsius) with the use of oxygen. Incineration requires specialized equipment with a dedicated fuel source. Simply burning deadstock on-farm in a burn pile or barrel is not considered incineration, and does not meet emissions standards for combustion.

- operating incinerators may require adherence to special codes, acts or regulations, so check for regulations in your province. Follow guidelines to avoid neighbors’ complaints

- carcass volume is efficiently reduced to ash

- process destroys infectious agents, including prions

- residue does not attract rodents or insects

- the purchase of an incinerator requires a significant capital investment

- incinerator ash is still considered SRM and cannot leave the farm of origin (unless properly transported to an authorized landfill)

- there could be safety issues related to high-temperature incinerators

- incineration services are not available everywhere

Burial on-farm or in an authorized landfill

With proper management, burial allows the deadstock to be disposed of quickly, and is convenient and inexpensive. Burial options must comply with provincial and municipal standards and requirements.

On-farm burial pits should be located in clay or till soils, away from water sources. Always do a test hole to a depth of about 4 meters, and wait for 24 hours to ensure no water seeps in.

- an adequate site is required to avoid groundwater pollution

- burial may allow for the disposal of a large number of carcasses

- multiple sites may be required, depending on the amount of deadstock

- it will be difficult or impossible to dig a burial site in winter

- the site may need to be managed for years until the decomposition is complete

- if BSE is suspected, other methods must be used to dispose of the carcass

- timely closure of the pit with top soil can prove challenging

- public perception of this method of disposal is unfavourable

At one time, off-farm authorized landfills were widely available for disposing of deadstock. With the advent of BSE, these options are more limited than before, and are not available in all geographic areas. Check with your local municipal landfill office to see if this option is available in your area and be sure to adhere to the permit procedures for transporting SRM.

On-farm animal mortality collection services

In some areas, on-farm pick up of deadstock is available from licensed companies that have specially designed trucks to make collections in a timely manner. Minimum weights may apply and costs for producers will vary. Deadstock pick up is not available everywhere. Search online for “on-farm mortality management” or “deadstock pick up” in your province.

On-farm composting

Composting is a controlled and naturally occurring process that uses bacteria, fungi and other microbes to convert organic material into a humus-like material, through the use of carbon, nitrogen, water and oxygen.

With composting, materials are reduced and most (but not all) pathogens are destroyed. Farm composting of deadstock is a safe method of disposal, if the material to be composted does not include prions or other high-risk pathogens.

- composting is relatively simple and inexpensive as it uses materials available on the farm (litter, straw, manure)

- locate compost site away from farm houses, water sources and wells, pastures and roads

- compost design should limit access to scavengers

- composting is a practical year-round process

- for large herds or intensive operations, a large land base will be required to support composting

- composting can be a labor-intensive process that requires vigilant management

- it can take up to nine months for a composting carcass to decompose

- proper carbon to nitrogen ratios, moisture levels and adequate aeriation are required for successful composting

- prions in SRM may not be completely destroyed through composting

Federal regulations prohibit the sale or removal of on-farm composted material containing SRM from the farm of origin without a permit. Producers planning to re-use composted materials containing SRM on the farm should note that researchers feel more information on the safety of this is required. Previous laboratory-scale composting research using BSE-infected SRM showed that not all prions were destroyed through composting – only between 90% and 99% of prions were destroyed.

Tim McAllister and Shanwei Xu’s on-going research into composting SRM has found that composting is a viable method for the controlled disposal of SRM in Canada. Click here for more information. You can also view our webinar on disposal of cattle mortalities.

What are the issues and research going forward?

The challenge for producers is that not all SRM disposal options are available to them locally, and options that are available could be cost-prohibitive.

Techniques for the disposal of SRM continue to evolve. New research strives to uncover more efficient and scientifically based ways for the industry to ensure food safety while maintaining the vitality and profitability of the cattle industry.

Ac cording to the 2012 Review of the Enhanced Feed Ban, over 90% of SRM is being confined in Canadian landfills, with no conversion to other products. Depending on the disposal methods a producer has access to, increased costs to cattle producers may decrease Canada’s international competitiveness.

cording to the 2012 Review of the Enhanced Feed Ban, over 90% of SRM is being confined in Canadian landfills, with no conversion to other products. Depending on the disposal methods a producer has access to, increased costs to cattle producers may decrease Canada’s international competitiveness.

Since the Enhanced Feed Ban, initiatives that aim to reduce SRM confinement in landfills have been explored. If a method of composting can be found to effectively destroy all prions, and show that there is no prion uptake by plants, SRM may have further uses as fertilizer.

Tim McAllister, Ph.D. and Principal Research Scientist, Ruminant Nutrition & Microbiology with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, and Shanwei Xu with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry at the Lethbridge Research and Development Centre, completed research in 2013 that looked at what happens with prions when composting SRM. They found that composting is unlikely to completely destroy all prions but that long composting periods can reduce prion infectivity by at least 90%.

They are currently collaborating with Stephanie Czub of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency on new research on composting methods for SRM that builds on this 2013 research. They are conducting research using larger-scale methods than the previous research which used a garden-scale compost system. This new research will mimic composting in ‘real-world’ conditions on the farm to investigate the effectiveness of on-farm cattle composting.

These ongoing research projects are laying the scientific groundwork for further improvements in dealing with SRM.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info [at] beefresearch [dot] ca

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Tim McAllister from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Karin Schmid from Alberta Beef Producers, and Rob McNabb from the Canadian Cattlemen's Association for contributing their time and expertise to this page.

This topic was last revised on August 29, 2018 at 1:08 AM.

View Web Page

View Web Page View PDF

View PDF