Dark Cutting Beef

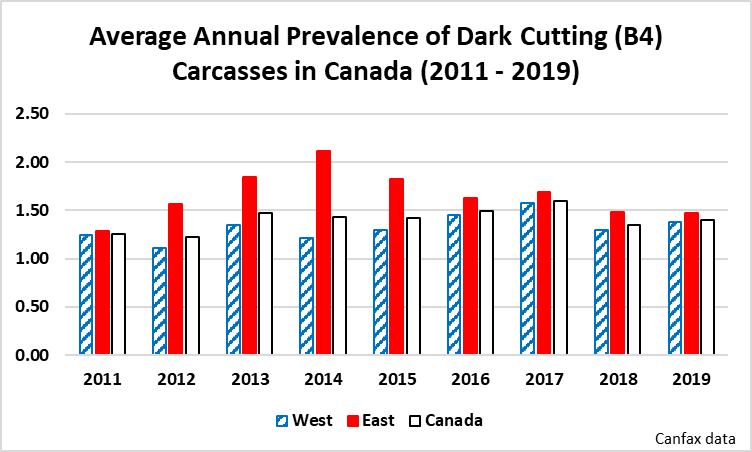

Dark cutting is a stress-related condition that is severely penalized in youthful (under 30 months) carcasses within the Canadian grading system. Carcasses that ‘cut dark’ are assigned a grade of Canada B4 and their value is reduced by up to 50 cents per pound. Canada’s 2016/17 National Beef Quality Audit estimated the cost of dark cutters to Canada’s beef industry at $10.6 million. In 2019, 1.4% of fed slaughter carcasses in Canada graded B4.

On this page:

Key Points

|

Canada B4 Grade

|

Up to $300 in value can be lost per head of cattle that grade Canada B4. |

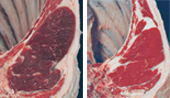

The ribeye of dark cutting carcasses is very dark red to purple, unlike the expected bright red colour. Dark cutting occurs when cattle are physically stressed prior to slaughter and muscle glycogen (energy) is depleted from the muscles, resulting in an elevated muscle pH (pH above 5.8). Beef from dark cutters is visually unappealing to consumers, and the high pH stimulates the growth of spoilage bacteria, reducing shelf life.

Dark cutting beef is visually unappealing to retail consumers, has a shorter shelf-life, and is tougher than typical beef.

Cause of Dark Cutting

|

|

Dark cutting is a sign that cattle have been physically stressed and have depleted the energy reserves of their muscles prior to slaughter.

Muscles remain active after an animal is slaughtered. These metabolic processes are powered by glycogen, the molecule that stores energy in muscle. Glycogen is a chain of glucose sugar molecules, similar to the starch that green plants use to store energy. Glycogen levels in the muscles drop when animals are active, stressed, and/or deprived of feed.

Normal vs. dark cutting carcasses

|

After slaughter, the lungs and heart stop and the circulatory system stops delivering oxygen to the muscles. The muscles quickly run out of oxygen, and switch from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism. In a normal carcass, anaerobic metabolism converts glycogen to lactic acid. As the lactic acid accumulates in the muscle, the pH of the muscle drops from 6.9 (normal) to 5.5 (acidic). At this pH, the iron in the oxygen-carrying muscle protein myoglobin can bind to oxygen from the atmosphere and produce a bright red colour.

In contrast, the carcass of an animal that has been stressed, overly active or feed deprived has less glycogen available to fuel the anaerobic metabolism. Less lactic acid is produced, the pH doesn’t fall as much, the colour change doesn’t occur, and the muscle remains a dark red or purple colour.

Since dark cutting is related to muscle energy (glycogen) levels, it follows that risk factors for dark cutting beef are related to situations that demand muscle energy but don’t allow it to be restored.

Known Risk Factors

Dark cutting is more common in late summer and early fall, and generally tends to be more common in Eastern than Western Canada. This may be related to regional weather differences, management and marketing practices.

Aggressive activity

Bulls tend to produce dark cutting carcasses, particularly if they are mixed prior to slaughter because they engage in fighting and mounting to re-establish social order.

Estrus

Heifers can also produce carcasses that cut dark if estrus behaviour is not inhibited by melengesterol acetate (MGA) or spaying. Heifers that have been off MGA for more than 48 hours before slaughter will start cycling and be at a higher risk of dark cutting (in Canada, cattle fed rations containing MGA must not be slaughtered until at least 24 hours have passed since their last access to feed containing MGA.

Stress

Cattle that are transported long distances, wet and cold and shivering, mixed with unfamiliar cattle or stressed (e.g. auction marts) or re-sorted multiple times just prior to slaughter are also at substantially increased risk of dark cutting.

Growth promotants

Extremely aggressive implant programs may be a risk factor for dark cutting. Some growth implants skew bovine muscle metabolism toward using glucose immediately for muscle growth. This can reduce muscle glycogen reserves and prevent muscle pH from declining to the normal post mortem pH value of 5.5 after slaughter.

Weather

Dark cutting is most common during the hottest months of the year, during late summer and early fall. This is true in both Eastern and Western Canada. It is uncertain if this is due to humidity and heat stress, or the variability between hot days and cool evenings.

Mitigation

When cattle engage in aggressive activity, estrus or stress, muscle glycogen can deplete quickly. Glycogen can only be restored by muscle after a period of rest. Cattle that have been severely stressed may require a rest period in order to completely recover.

In most cases, stressed animals should be rested overnight to prevent dark cutting. If severe depletion has occurred, up to 4 days rest with feed can be required to return glycogen levels in muscle to normal.

Feed or water supplements have also been shown to help restore electrolyte balances after a period of stress. Some commercial products, including the Canadian product DeStress, can help animals recover from transport stress and prevent dark cutting, provided intake is adequate. These products may not always be cost-effective when used to prevent dark cutters because they need to be given to all cattle, even though only some may be at risk of cutting dark.

The second Beef Science Cluster funded a project to see whether live animal characteristics or genetic markers could be used to identify cattle at heightened risk of dark cutting. This research was led by Dr. Heather Bruce with colleagues at the University of Alberta (Walter Dixon, Steve Miller, Graham Plastow) and collaborators from Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development (John Basarab) and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (Jennifer Aalhus).

Potential animal predictors were evaluated using two data sets collected over an eight-year period. The first data set examined 180 steers and heifers from one farm that had live animal and carcass measurements. The second data set included data from 467 heifers from three farms, including heifers from the first data set. Weaning weight, live slaughter weight, dry matter intake, average daily gain, feed conversion ratio, residual feed intake, ultrasound and actual carcass measurements, animal age, and days to finishing and age at slaughter were recorded. Cattle were also grouped according to whether their post-transport and pre-slaughter rest times were 4, 5, 6, 10 or 72 hours. The cattle that were rested for 72 hours received both feed and water, while the cattle with the shorter rest times were provided only water.

Genetic markers were assessed in 80 ribeye samples from AA and B4 carcasses from a commercial abattoir on two separate occasions. The carcasses came from 24 different groups of cattle that were the same gender, originated from the same feedlot, and were transported together. The ribeye measurements included pH, shear force, colour, water holding capacity, nutrient analysis, myoglobin estimation, muscle fibre length, glucose metabolism, proteomic and genetic analysis.

What they learned: The frequency of dark cutting was higher in heifers than steers. Both carcass weight and live weight were related to the probability of a heifer having a dark cutting carcass, with lighter, slower growing animals more likely to cut dark. In steers, there were some instances of very large, heavily muscled steers also cutting dark. The relationship between carcass weight and dark cutting was stronger than that of live weight and dark cutting, which suggests that there may be other factors involved. Generally, heifers weighing over 1200 lbs live, and with carcass weights over 715 lbs had a substantially lower risk of dark cutting. The amount of marbling was not related to dark cutting, with the marbling in dark cutting carcasses similar to AA carcasses. No single live animal or carcass phenotype was associated with dark cutting, as there was at least one dark cutting carcass spanning all the different heifer phenotypes. Animals that were slaughtered after a longer post-transport wait period were more likely to be dark cutters. Previous research has shown varying results when comparing post-transport and pre-slaughter times. Some research has shown that longer rest times reduce the proportion of dark cutting carcasses, while other results support this study’s findings. A large part of these contrasting results may be due to management during that rest period, including when feed and water is provided, and the quality of that feed. In this study, heifers and steers that were slaughtered the day of shipment were least prone to cut dark when held for 5-6 hours before slaughter compared to the other time periods.

A small number of carcasses had a normal pH, but still exhibited the dark cutting colour characteristics. These atypical dark cutting carcasses had a slow rate of post mortem glucose metabolism, reduced activity of the enzymes that break down glucose and proteins and produce tougher beef than typical dark cutting carcasses.

Genetic analysis found 924 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) located near 19 candidate genes. These areas will have to be analyzed more completely to determine if there is a genetic component that accounts for a large degree of the variation in atypical dark cutting between animals.

What it means: Dark cutting is a multi-factorial condition caused by the interaction of numerous management and animal factors. This research demonstrated that lighter, slower growing heifers are most likely to cut dark. It may be possible to identify animals at risk of dark cutting based on animal weight, average daily gain and feed intake. Differences exist in the enzymes that control the metabolism of glycogen between normal and dark cutting carcasses. Further research may reveal fundamental metabolic or genetic difference in dark cutting cattle.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Heather L. Bruce, University of Alberta Associate Professor of Carcass and Meat Science, for contributing her time and expertise to writing this page.

This topic was last revised on March 9, 2020 at 2:03 AM.

Dark cutting beef (left) is a dark red to purple colour, compared to the normal bright colour of typical beef (right). Photo courtesy of the Canadian Beef Grading Agency.

Dark cutting beef (left) is a dark red to purple colour, compared to the normal bright colour of typical beef (right). Photo courtesy of the Canadian Beef Grading Agency. View Web Page

View Web Page View PDF

View PDF