Water Systems For Beef Cattle

Water is an essential nutrient for cattle, accounting for between 50 and 80 percent of an animal’s live weight. For livestock to maximize feed intake and production, they require access to palatable water of adequate quality and quantity. Factors that determine water consumption include water quality, air and water temperature, humidity, moisture content of feed/forage, cattle type (calf, yearling, bull, cow) and the physiological state of the animal (gestation, maintenance, growing, lactating). Producers must consider individual grazing management strategies, site characteristics and economics when designing water systems.

Water is an essential nutrient for cattle, accounting for between 50 and 80 percent of an animal’s live weight. For livestock to maximize feed intake and production, they require access to palatable water of adequate quality and quantity. Factors that determine water consumption include water quality, air and water temperature, humidity, moisture content of feed/forage, cattle type (calf, yearling, bull, cow) and the physiological state of the animal (gestation, maintenance, growing, lactating). Producers must consider individual grazing management strategies, site characteristics and economics when designing water systems.

On this Page

- Key Points

- Water Requirements

- Water Quality and Potential Issues

- Water Systems and Sources

- Improving Pasture Utilization with off-site Watering Systems

- Designing a Water System

- Calculating the Costs of Water Systems

Key Points

|

Water Requirements

For optimum health, cattle need a consistent source and adequate supply of water on a daily basis. Water quality and intake will affect cattle growth and performance. Access to fresh, clean water increases animals’ water intake, which in turn, increases their dry matter intake. This improves animal performance.

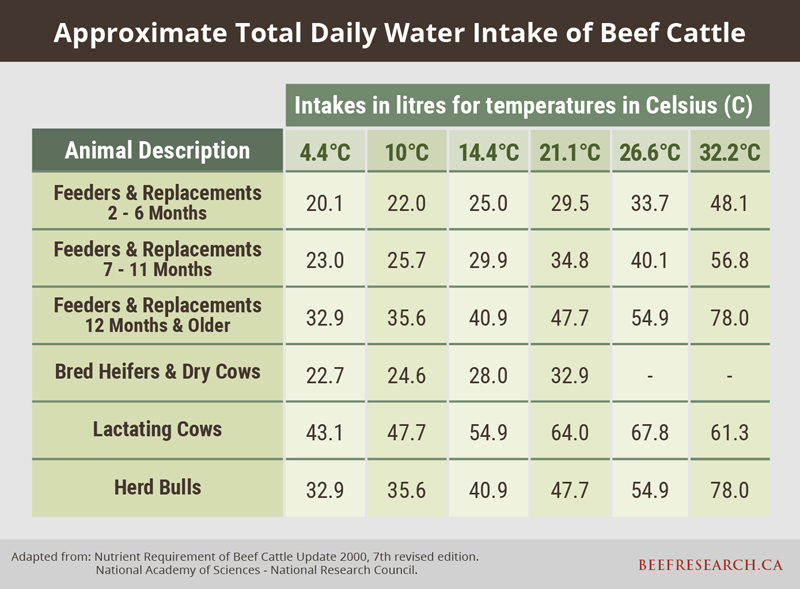

Water consumption will vary based upon water quality, air and water temperature, humidity, moisture content of feed/forage, class of livestock, animal weight, and the physiological state of the animal. Heavier cattle have greater total daily water intake requirements as do lactating cattle compared to non-lactating cattle. Minimum water requirements are needed for growth, fetal development or lactation, water loss through urine, feces, sweat, or evaporation from lungs or skin. Factors that influence these needs will impact water requirements. For example, if cattle consume a diet high in protein, salt, minerals or diuretic substances, water needs will increase. If environmental temperature or physical activity increases, water losses through evaporation and sweating will also increase, resulting in increased water needs1.

When designing a water system, the following guidelines on consumption will assist with calculations for capacity. Calves less than six months of age can consume between 20 to 50 litres of water per day depending upon temperature, while growing cattle can consume between 30 and 78 litres daily. Lactating cattle require 40 to 60 litres per day. All cattle will consume greater amounts of water during hot weather2.

Water Quality and Potential Issues

As a key nutrient required by cattle, water of suitable quality must be provided consistently to meet drinking needs. While cattle can be maintained on lower quality water sources, their health and performance can be negatively affected. Conducting baseline water tests to determine important parameters of water quality will assist producers in identifying whether a water source is suitable.

As a key nutrient required by cattle, water of suitable quality must be provided consistently to meet drinking needs. While cattle can be maintained on lower quality water sources, their health and performance can be negatively affected. Conducting baseline water tests to determine important parameters of water quality will assist producers in identifying whether a water source is suitable.

While cattle can often tolerate or adapt to certain factors that reduce water quality, periodic testing of the water will assist with identifying the factors and indicate levels that may be problematic. Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) measured in milligrams/litre (mg/L) or parts per million (ppm) is the main indicator of water quality and is a measure of the total concentration of dissolved inorganic salts in water. Factors that can impact TDS and compromise water quality include excessive mineral levels, high or low pH levels, sulphates, nitrates, salinity, algae and bacteria. Weather events, such as excessive rainfall and flooding, or periods of drought can impact water quality. Evaporation of water can exacerbate these factors and create issues with increased bacteria, algae, or concentrated TDS levels which can impact cattle health, weight gain and immune function.

Alkalinity - is usually expressed as pH, with readings of 7.0 being neutral, levels below that classified as acidic and levels above that classified as alkaline. Alkalinity measures water’s ability to neutralize an acid. Water pH in a range of 6.0 - 8.5 is acceptable for cattle. While water pH below 5.5 can cause acidosis, reducing feed intake and performance, most water used by livestock is mildly alkaline. When water pH becomes highly alkaline, nearing pH of 10, physiological and digestive upset can occur3.

Algae - Stagnant, slow moving bodies of water, high in nutrients, particularly phosphorous or nitrogen, are more prone to increased growth of algae. It is important to control nutrient accumulations in water by providing off-site watering systems that limit direct livestock access to the water source, aeration to keep the water moving, and reducing run-off into water bodies. Regular monitoring of water sources is essential.

Blue-Green Algae (Cyanobacteria) – Blue-green algae is not an algae but rather a bacteria called cyanobacteria. Certain types of this bacteria can produce toxins that can cause liver damage, gastroenteritis, loss of coordination and sometimes death in livestock. With large amounts of consumed toxin, paralysis and respiratory failure occurs rapidly, within minutes, as the cattle suffocate4. Proper identification is key before treatment as it is often mistaken for duck weed, which is a beneficial aquatic plant. Heavy blooms appear to be solid green across the water; some species look like pea soup or grass clippings. The bacteria lives within the water column so it flows with the water when letting water run through your hands. Watershed management helps minimize cyanobacteria. Prevent nutrient inputs such as phosphorus, nitrogen, animal waste, fertilizers, soil particles, and silt. Each of these acts as a fertilizer for algae and aquatic plants. Preventing direct access to water sources through the use of remote livestock watering systems can reduce problems. Treatment options include dyes, aeration, or a variety of registered copper sulphate products. After treatment, access for livestock should be restricted for 12-14 days, as the toxin is released in higher amounts when the bacteria dies.

Nitrates - can be converted into nitrites by bacteria in the rumen. Nitrate toxicity from water is not common; however the combination of nitrates in feed together with those in water can create nitrites which diffuse into the blood stream causing respiratory distress and even death. When nitrate levels climb above 100 mg/L and are combined with feed containing nitrates, cattle may be at risk4. Run-off from farmed fields may create additional risk of accumulation in water bodies.

|

When high nitrate feed and water are consumed in combination, toxic levels can be reached resulting in death 3-5 hours after consumption. |

Salinity - is the concentration of dissolved salts, such as calcium, magnesium and sodium chloride. It refers to the mineral content of water. The salinity of a water source can change over time. Salinity can increase with evaporation during hot, summer months. Young animals and lactating cows are at greater risk of harm from salinity. Cattle can adapt to certain concentrations of salinity over time; however abrupt exposure to high salinity water sources can be problematic. Cattle will generally avoid drinking water that is too salty, but if it is the only water source available, they will eventually become too thirsty and over-consume, which can lead to death.

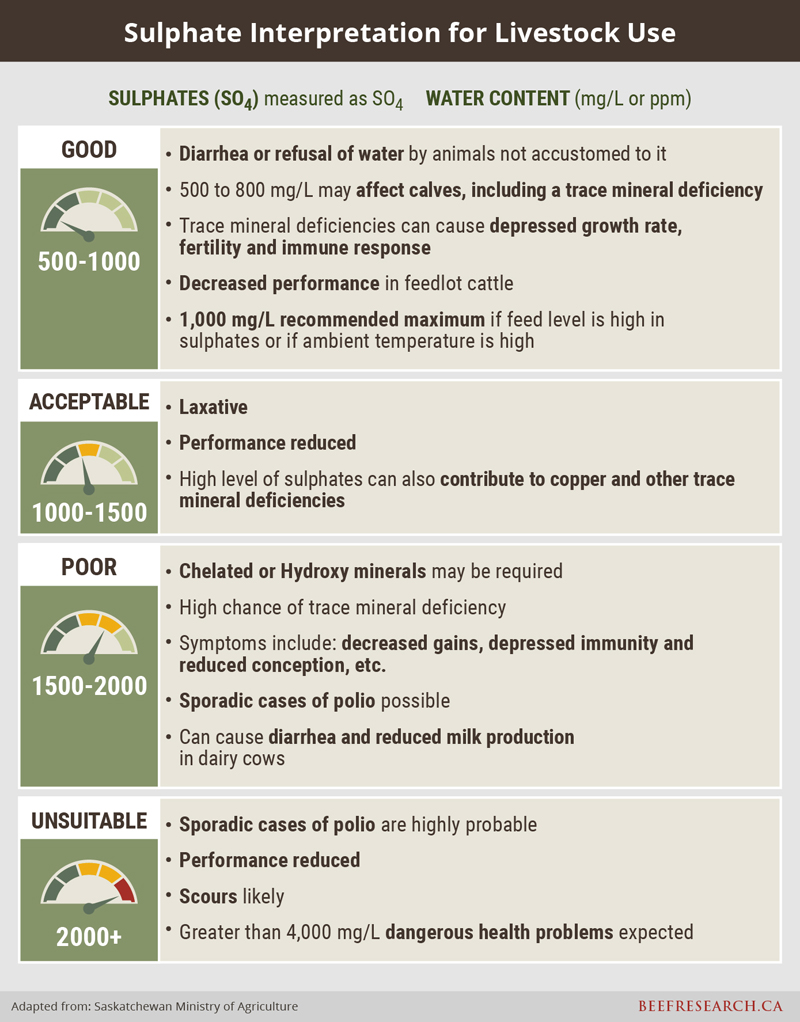

Sulphates - are common in groundwater on the Prairies and have also been found in spring-fed dugouts and surface sources that drained from saline soils. Sulphates can affect trace mineral metabolism, causing a deficiency of copper, zinc, iron and manganese. These deficiencies can lead to depressed growth rate, infertility, skin integrity and poor immune response. Sulphates can cause diarrhea when levels reach 500 ppm, and at higher levels, can cause animals to reduce their water consumption. At levels of 500 to 1000 ppm (parts per million), trace mineral deficiencies can be induced which may reduce growth and fertility. At sulphate levels over 2000 ppm, cattle may develop polioencephalomalacia (PEM) which is characterized by blindness, difficulty walking and seizures. Note that research is currently underway to further refine sulphate recommendations and better understand the production impacts of varying levels of sulphates.

The following table lists water constituents that can affect beef cattle performance, as well as levels that are unsuitable.

The blog, What’s in Your (Stock) Water discusses some of the concerns about what could be lurking in water sources.

Water quality can change from year to year, and in certain instances, can even change over the course of a season. Do not rely on past analysis. Conduct water tests regularly; annual testing is preferred during normal circumstances. Weather conditions such as drought, can quickly impact water quality. If changes in water such as smell, clarity and taste, or changes in animal performance, or eating and drinking habits are noticed, re-test immediately.

|

Water quality can change from year to year, and in certain instances, can even change over the course of a season. Do not rely on past analysis. Conduct water tests regularly; annual testing is preferred during normal circumstances. |

Run-off, flooding and drought can impact water quality. Periodic water testing, and increased vigilance during times of drought will help prevent animal health issues due to increased levels of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS). Recent drought on the Prairies raised TDS levels in many water sources, compromising cattle health and resulting in the deaths of a number of animals. Over half of Saskatchewan livestock water sources tested recently (600 water sources) indicated unsafe levels of sulphates and TDS. While handheld meters that test for electrical conductivity can provide a quick test, and an indication of quality, due to the correlation with salts and electrical conductivity, they are not as accurate as a lab analysis.

The BCRC webinar, What’s in Your Water? Water Quality and Economics of Pump Systems, explains that TDS does not equal conductivity and provides information on water testing to prevent animal health issues.

The Rural Water Quality Information Tool is an online tool that allows producers to input water quality testing results to ensure suitability for livestock.

Water Systems and Sources

Water systems can be designed that utilize either ground water or natural sources. Water can then be pumped to a bowl or trough, through pipelines, to nose or other pumps, or to reservoirs. They can be powered by electricity, solar energy, windmills, gravity, gas or diesel engines, and even cattle, in the case of nose pumps.

Seasonal changes in weather will impact water sources and systems. While cattle are able to water from sources such as dugouts, lakes and sloughs during summer months, access to these sources is more difficult during winter months. Chopping frozen dugouts or lakes to water cattle requires more labour, creates challenges for cattle accessing the water, and has the additional risk of animals breaking through the ice and drowning. Water sources need to provide safe access, with solid footing to ensure cattle consume adequate amounts.

Cattle can negatively impact natural water sources when free access is permitted. Reduce and manage access to wetlands to preserve riparian areas. Cattle can destabilize the bank, accelerate erosion, damage vegetation and the nests of grassland birds, and reduce water quality. When cattle have direct access to water sources, they will defecate in and around the edges of the water body. This can introduce pathogens as well as nutrients that contribute to excess algae growth, which can produce fatal toxins. Cattle who linger in water sources may experience higher rates of foot rot5. Allowing access can also reduce the lifespan of the dugout through the degradation and erosion that can occur. Where possible, fence cattle out of water sources.

Fencing off water sources and pumping to a trough improves water quality and reduces water losses. Clean, pumped water can improve herd health, weight gain and backfat. Water consumption and forage intake are closely related; when cows drink more water, they spend more time grazing, and produce more milk for their calves.

Fencing off water sources and pumping to a trough improves water quality and reduces water losses. Clean, pumped water can improve herd health, weight gain and backfat. Water consumption and forage intake are closely related; when cows drink more water, they spend more time grazing, and produce more milk for their calves.

Research from two separate studies in 2002 and 2005 found that calves who drank clean water from a trough gained up to 9% more weight, an average of 18 pounds each, than the calves who drank directly out of the dugout. Yearlings gained 23% more when drinking clean water, rather than drinking from a pond6. For more information, see the blog post on water systems here.

|

200 calves have access to fresh, clean water and gain 9% more weight 500 pound calves X 9% = 45lbs extra weight per calf 200 calves x 45 lbs/calf = 9,000 lbs @ $2.00/lb = $18,000 additional income. While individual results will vary, investing in water systems to ensure fresh, clean water sources can create a positive return to producers. |

Benefits of well-designed water systems that provide a quality water source include:

- increased weight gain

- improved herd health and reproductive performance

- safer watering sites

- increased longevity of water source

- enhanced wildlife habitat

- environmental benefits, including improved riparian health and reduced erosion

- improved pasture utilization

Improving Pasture Utilization with off-site Watering Systems

Access to a reliable, quality water source can be a limiting factor in pasture utilization. When using pastures and water sources that are not in close proximity to electricity, other power sources, such as wind, solar, and animal can be used effectively to operate the system. These remote/off-site water systems and alternate power sources afford producers greater flexibility with grazing management and pasture utilization. This can also extend grazing into fall and winter, reduce overgrazing of certain areas, improve manure distribution, reduce direct access to ponds and dugouts to keep water sources fresh, and reduce risk of injury to animals. Strategic placement of these water systems improves utilization of pasture and reduces impact on riparian areas7.

Designing a Water System

Conducting an inventory of existing resources and determining how the needs and objectives for the new water system align with those resources, will help when designing the system best suited for each operation. Consider the following factors:

- grazing management system

- herd size and animal type (yearlings, cow/calf, bulls, dry cows)

- site characteristics and availability of water sources

- season of use

- proximity to electricity or alternate power source

- cost to install, maintain and operate

- labour and time to check the system

- desired flexibility - portable system, trough, water tanker, shallow pipelines

Individual grazing management systems will impact water system design and development. Continuous, simple rotational and intensive or mob grazing systems may each require different water sources and systems. When water is supplied to paddocks of ten acres or less, cattle tend to drink individually. When water sources are centralized in a larger pasture, cattle tend to move as a herd and drink as a herd. Ensure adequate flow or capacity to accommodate the entire group in under twenty minutes to avoid excessive competition among animals8. In those instances, younger or weaker animals may not have a chance to drink enough before the herd moves off to graze again.

Grazing management systems that include mob grazing and electric fencing may use a portable water system, shallow pipeline or water truck and trough. In systems where cattle are in small paddocks or pastures, and are drinking individually or in small groups, large troughs are not usually required as long as water flow can be maintained while the animals drink. Rotational grazing systems can incorporate water systems such as shallow pipelines or fenced dugouts that pump to a larger trough, as the cattle will generally drink as a herd. Continuous grazing systems require water sources that can accommodate the entire herd at once, and ideally, water sources should be located so cattle can access without travelling over 240 metres (800 feet)9 to avoid overgrazing in areas close to water or under grazing in areas located further away from water sources.

Site characteristics and availability of water sources will influence the type of water system. Conduct an inventory of the site to match appropriate water systems that will function well within the area. Consider the desired time of grazing for the pasture as that will also influence the system selected. While dugouts can be effectively fenced out and pumped into troughs from spring to fall, winter systems require components that can remain frost- and trouble-free during extended cold periods.

Power sources are a key consideration when designing a water system. While electricity is often considered to be the most reliable power source, the cost to run power to systems can be prohibitive; therefore many alternate power sources are now available to operate off-site water systems. Costs to install, operate and maintain the water system must also be considered. Wind is a relatively inexpensive power source. Solar is a bit more expensive, with the batteries to store extra power contributing to the overall cost. Reliability is important, as systems need to be checked and maintained to ensure a consistent supply of water to livestock.

|

When implementing a stock water system, make sure that the system has ample storage capacity and that it is checked regularly. Consider a back-up water supply in case of a system malfunction to ensure that livestock have a steady supply of water. |

Systems such as portable solar powered troughs or tankers and troughs can offer more flexibility and often reduce costs, as they can be moved to multiple paddocks through the season, improving pasture utilization.

In these photos, 1000 pairs of cattle and bulls are mob grazing at TeeTwo Ranch near Kelliher, SK and drink from a customized water truck with tanks. The truck holds 38,000 litres (10,000 gallons) and the three tanks hold about 1,800 litres (500 gallons).

Tankers and water system for intensive grazing system. Photo credit Duane Thompson.

Close up of tanks. Photo credit Duane Thompson.

Portable water troughs provide flexibility in various grazing management systems. Rotational grazing can be enhanced by using remote, portable systems. Recent research demonstrated that when given a choice, eight out of 10 cows will drink from a trough rather than a dugout or river10.

The following video clip highlights cattle’s preference to drink out of troughs, rather than wading into streams or dugouts.

Shallow pipeline systems can be an effective and cost-effective way to water cattle in large pastures, accommodating continuous and rotational grazing management. Shallow pipelines effectively use the convenience and reliability of electricity to pressurize a tank and push water to distant pastures and create remote water troughs that can assist with more effective pasture utilization. Pipelines can be trenched into pastures, ranging from simple systems consisting of one to two miles (1.5-3 kilometres) of pipeline servicing a few troughs, to extensive systems supplying water to numerous troughs. These pressurized systems require 1) a water source, 2) a power source, (electricity is most common due to reliability and the large number of batteries that would be required with a solar power source) 3) a pump, 4) pipe, valves and fittings, and 5) troughs. Pipelines are seasonal and need to be blown out prior to freeze up to avoid damage11.

Groundwater Sources

Wells - can be bored or drilled, depending on depth to aquifers. Bored wells are usually constructed where the groundwater is less than 30 metres from the surface and are often large-diameter installations. Drilled wells are constructed to reach much greater depths and are smaller in diameter. Bored wells are more likely to be affected by variations in precipitation and recharge than drilled wells. Both types will require a pump to extract the water12.

Springs - occur where groundwater emerges naturally on or near the ground surface. The surface point of the spring may be a small part of the water-bearing area. Excavation parallel to the land at, or below the surface point, and installing drainage pipe or cribbing can increase the flow and protect the spring. To ensure that the spring keeps flowing, several steps should be taken when developing springs as a water source for livestock. 1) Ensure that the spring does not get contaminated by surface runoff. 2) Fence livestock out to prevent trampling by animals and pipe the water to a remote site. 3) Avoid altering the spring by building dams or embankments. In some instances, this construction causes the spring to stop flowing due to the rise in water level where the spring discharges12.

Source: Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, Spring Development Fact Sheet. 2002.

Spring fed ponds - are naturally occurring water bodies that can be used for livestock watering. While allowing direct access by livestock is cost effective and easy in the short term, this can damage banks, reduce water quality and shorten the life and capacity of the water source. In spring fed ponds, where shallow aquifers exist, surface water can mix with groundwater. Groundwater is usually highly mineralized and surface water is susceptible to microbial contamination. To ensure continued flow and water quality, fence cattle out of the water body and use remote systems like nose pumps or troughs. Avoid introducing contaminants into the aquifer13.

Photo credit Tamara Carter

Surface Water Sources

Dugouts - are the most common water source for grazing cattle and are recharged by surface water such as snow and field drainage. Dugouts are man-made water sources and generally provide adequate quality water for livestock. Site selection is important to ensure a long-lasting source of quality water. Low lying areas that appear to be suitable for dugout construction may have salinity issues, runoff challenges, or high Total Dissolved Solids (TDS).

During sustained periods of hot weather, evaporation can also increase levels of TDS and salts, which can result in reduced water consumption, poor performance and even death. As dugout water is usually stagnant (non-moving), algal blooms may be a concern at certain times of year. Conduct water tests to ensure that water is within safe levels of salinity, TDS, nitrates and sulphates.

To avoid entrapment or drowning by cattle breaking through ice in the winter, fence cattle out of dugouts and use a pump or remote system to pump water into a trough. Pumping to a trough and restricting access to the dugout will also preserve the dugout banks from damage and erosion and prevent cattle from contaminating the water with feces. Research that examined improving water quality through aeration and pumping to a trough showed increased weight gains of approximately 10% over 90 days14.

As with spring fed ponds, dugouts that hit shallow aquifers are best fenced to restrict direct access by cattle. Water levels may rise during high water recharge; however during droughts when groundwater levels fall, water in the dugout may drain into the aquifer. This can introduce contaminants into the aquifer13.

Photo credit Jeremy Brown

Preventing direct access to dugouts can reduce E. coli (Escherichia coli) in water. Dugouts in rural areas that are not used as a water source for cattle, have been found to have E. coli counts of 20 to 100 per 100 mL, with wildlife being the source. When cattle have direct access to dugouts, E. coli counts can increase to over 10,000 counts per 100 mL in extreme cases. Using this source for other purposes, such as watering a vegetable garden, could create a health risk.

Sloughs - are naturally occurring surface water sources which generally occur in low-lying areas that collect snow and rain runoff. They can provide adequate water quality to most cattle. As with dugouts, hot, dry weather conditions can create increase salinity and TDS to dangerous levels. Shallow sloughs with salt rings can be an early indicator of potential salinity issues. Testing with an electrical conductivity meter (EC) will provide information on salt levels. Sloughs are also at risk for the formation of blue-green algae, which is bacteria that proliferates during warm weather in stagnant water. It produces toxins which are dangerous to cattle.

Rivers, streams, lakes - can provide good quality water to livestock, but allowing cattle direct access to these sources can damage riparian areas, banks and habitat for other wildlife. As with dugouts and sloughs, cattle will walk into the body of water to drink and cool off during summer months, urinating and defecating in the water. Cattle may be at risk of drowning or entrapment, depending upon the banks and water current. Where possible, fence cattle out of rivers, streams and lakes, using troughs, nose pumps, or other systems to keep cattle out of the water source. This will preserve riparian health, reduce contamination of water, and extend the lifespan of the water source.

Photo credit, Tamara Carter

Snow - can provide adequate water to meet the needs of dry cows when it is clean, loose, and not frozen solid or crusted over; however, lactating cattle, newly weaned calves and thin cattle (body condition score less than 2.5 out of 5) require an additional water source. Using snow for a water source requires energy in the form of body heat to melt it into water, so snow alone is not sufficient for animals with higher energy requirements. New cattle may need several days to learn to eat snow. The BCRC blog Is It Ok to Use Snow as the Only Water Source for Cattle? provides more information for producers relying on snow for water.

Powering the System

There are many ways to effectively supply power to water systems, which will vary with the water source, the herd size and type of cattle, compatibility with the watering system selected, and the cost. Some systems will operate with multiple power sources such as a combination of solar and wind to ensure batteries are sufficiently charged to maintain water capacity. New technologies such as motion detectors, drones, and cameras can assist producers in overall water system operation and monitoring. For all systems, the use of insulated tanks helps to keep water from freezing during cold weather.

Electricity - is the most reliable power source for systems that are in close proximity to current electrical infrastructure. It is able to lift water from greater depths. A common livestock water system is an automatic electric waterer, due to convenience, multiple season use, efficiency, reliability and long-term value. These systems consist of an insulated base and a heated bowl that fills from a pressurized line, maintaining water level with a float. Most have anti-siphoning valves to prevent back flow of water. These bowls are equipped with a thermostat, so are simple to operate during winter months. These water systems perform best when protected from wind and snow and when located on a concrete pad to provide firm footing for cattle and prevent shifting of the tank which can damage water lines and wiring. Waterers with dual bowls are an efficient way to increase utilization, by installing in a fence line to service more than one pen or pasture. Low energy versions of these bowls are also available with well insulated tanks and insulated covers. Small herds may have trouble keeping an adequate amount of water cycling through the system in cold winter months to keep it operating well. In very cold weather, these systems need to be checked several times daily, and may need to have the float thawed or knocked open in the morning15.

Photo credit Tamara Carter

Fossil Fuels or Propane - portable pumps hooked up to generators or propane tanks can be used to move water from a source to a trough. This can be time consuming as pumping generally needs to occur more frequently, and generators/propane tanks must be checked frequently.

Gravity fed - is a low-cost way to provide water, by using the existing landscape to direct spring water to a trough if it has the appropriate slope.

Solar - solar panels are durable, operate in a range of temperatures, and can remain operational for over 15 years. Solar panels can provide power to pumps in several applications. They can operate floating pumps in dugouts or can lift ground water from a well to a summer trough or insulated trough. When properly sized to fit the water consumption of the herd, they will generally keep from freezing and operate with little trouble during winter months. The use of a back-up power source provides extra reliability during cloudy periods. Deep cycle batteries can be protected in an insulated box to store power to keep up with pumping.

Solar powered water system. Photo credit, Tamara Carter.

Windmills - the rotary motion of the propeller drives a pump which moves water to a trough. They are simple, robust and cost-effective ways to supply water to livestock in areas where site conditions allow. There are three types of pumps used in windmills, with the most common being a positive-displacement cylinder pump. An alternative is the airlift pump, which has no moving parts and can lift water at rates between 20-2000 gallons (75-9000 litres) per minute, up to about 750 feet (230 metres) high16. Even in the windiest sites, wind power will vary, so a backup water system that stores extra water or a backup energy source such as a deep cycle battery is recommended. Windmills can also be used to aerate water sources, which can improve stagnant water quality.

Batteries - deep cycle batteries can be used to store energy in remote systems created by solar and wind. Match battery type to the system for best results. For example, flooded lead-acid batteries are cheaper to purchase, but require more maintenance to ensure reliable operation. Gel batteries are more expensive to purchase; however perform better in cold temperatures and may be more reliable in winter water systems17.

Water - sling pumps use a water driven propeller to create power. A sling pump requires a stream with a water velocity of at least 60 centimetres/second (2 feet/second) with a depth of at least 25-40 centimetres (10-16 inches) to operate18. There are few moving parts and very little maintenance.

|

|

Photo credit Jeremy Brown |

Animal powered - cattle can learn how to operate a nose pump to move a lever which pumps water into a bowl. Cattle activate the pump when they push and release a lever with their noses. The pumping action allows the water to enter a basin. The basin must be secured tightly so cattle are not able to push it around and it must be level to ensure that the water doesn't run out of the basin. Nearby water sources such as ponds, shallow water or a well can provide the water and the diaphragm pump has a maximum lift of 20 feet from the source to the bowl.

This system is suitable for small herds or groups. It only allows one animal to drink at a time, so it may not be a good choice with a continuous grazing system where all animals come to drink at the same time. To reduce competition, more pumps would be required. While prior information suggests that one pump can provide enough water for about 30 animals, some producers have successfully watered up to 100 head per pump, once cattle are well trained19. Multiple basins can be installed on top of an upright culvert to accommodate larger herds of cattle. Young calves may not be strong enough to pump this type of system and cows require a bit of training to learn how to use it. Monitor the system carefully when it is first installed to ensure all cattle learn how to use the pump and are getting enough to drink.

Winter tolerant nose pumps that operate year-round are another animal powered option. Rather than relying on a diaphragm to lift the water, the system employs a mechanical piston pump to draw water from a relatively shallow water source in the ground below the frost zone. The pump relies on geothermal heat and livestock power. This system has been observed to water 100 head per unit due to the unique pump action, supplying water on demand to cattle.

Photo credit Frostfree Nosepumps

Calculating the Costs of Water Systems

![]() When considering various water sources and designing an appropriate system, economic analysis and projections are helpful. The Beef Cattle Research Council’s Water Systems Calculator is a helpful tool. Producers can examine several different systems and input their herd size and cattle type (grassers, cow/calf) to calculate costs and time to pay off each system. After determining capacity, site conditions and grazing management, producers can estimate costs for the system most appropriate for their operation. Herd size, capital costs, and current calf prices will provide an estimate of how much time it will take to pay off the system.

When considering various water sources and designing an appropriate system, economic analysis and projections are helpful. The Beef Cattle Research Council’s Water Systems Calculator is a helpful tool. Producers can examine several different systems and input their herd size and cattle type (grassers, cow/calf) to calculate costs and time to pay off each system. After determining capacity, site conditions and grazing management, producers can estimate costs for the system most appropriate for their operation. Herd size, capital costs, and current calf prices will provide an estimate of how much time it will take to pay off the system.

Matching the water requirement with water system capacity to reach the optimum utility rate is a factor to consider when selecting and designing a livestock water system. Every operation will have different costs depending on their individual circumstances, and producers are encouraged to do a thorough comparison between viable options. Examining data from several water system types relative to calf prices, Canfax noted that in most scenarios solar pumping systems have the lowest initial cost compared to windmill and shallow pipe systems. Solar pumping systems also took the shortest time to pay off the initial cost. Herds of 100 head or less take a longer time to pay off the initial investment. As herd size increases, the per unit cost of a watering system on a per head basis declines, resulting in a shorter pay off period and higher net benefits. When factoring in the improved gains and health of livestock, these numbers can further be improved20.

The following table illustrates the number of years it can take to pay off initial costs based upon herd size, calf price and watering system selected.

Conclusion

Water, a key nutrient, impacts cattle health, immune function, rate of gain, quantity and quality of milk, and overall animal performance. Access to a palatable, high quality water source is vital. The quality of a water source may change over time; therefore, conducting regular water tests is recommended to ensure that the quality remains adequate. When weather conditions such as drought occur, decreases in water quality can be more severe and happen more quickly. In some instances, water quality will become unsuitable and will impact cattle health to the point of death.

Many different water systems are available; suitability will depend upon several factors, including herd size and composition, water sources, access to power, local geographic conditions, grazing management, and cost. The economics of a water system are dependent upon the initial cost, capacity, herd size, and cattle prices. Matching the water requirement with water system capacity to reach the optimum utilization rate by cattle is a major factor to consider when selecting and designing a livestock water system20. To ensure continuing quality, capacity, longevity and economics of a water system, while reducing herd health problems and impact on the environment, producers need to give careful thought to matching herd water requirements with grazing management, site conditions and economics.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us.

This topic was last revised on April 22, 2020 at 9:16 AM.