Transport

Ensuring the safety and wellbeing of beef cattle during transport is important to farmers, transporters, and the public.

Cattle transport in Canada is a critical element for beef production and marketing. Nearly all beef cattle are transported several times in their lives. Livestock transport has many components from start to finish and several things can impact animal health and well-being, and consequently meat and carcass quality. Using best practices for transport, including pre- and post-transport handling, can improve animal health and welfare in all parts of the beef value chain, from cow-calf through to feedlot operators, packers, and retail sectors.

Good transport outcomes require teamwork and communication between farmers, transport drivers, inspectors, and the final destination.

Photo credit: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

On this page:

Key Points

|

An Important Issue for Canadians

The public takes an interest in the welfare of cattle during transportation and handling. Most Canadians have little contact with farms and encountering cattle trailers on the highway may be their first point of contact with livestock. Scientific evidence and sound policies supporting Canadian beef cattle transport and handling regulations are increasingly valued by industry in order to maintain a social license to operate.

Transport Regulations and Codes in Canada

|

Canada’s Health of Animals Regulations and the National Farm Animal Care Council’s Transportation Code of Practice are currently undergoing amendments and updates. |

Livestock transportation in Canada is subject to regulations at multiple levels. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency, along with federal and provincial counterparts, regulates livestock transport in Canada under Part XII of the Health of Animals Regulations. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency is responsible for animal welfare during transport including aspects such as loading densities, potentially compromised animals, bedding requirements and duration of transit. Transport Canada’s Commercial Vehicle Drivers Hours of Service Regulations govern how often drivers need to stop for rest. Maximum trailer lengths and axle weight limits fall under provincial and territorial jurisdiction.

The first “Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals: Transportation” was developed in 2001. This code is currently under revision and is scheduled to be completed in 2023. This code provides industry standards and best practices for livestock transport and is designed to support regulations.

Canadian Research on Transport

|

Canadian research demonstrated that 99.98% of short haul (4 hours or less) and 99.95% of long haul (4 hours or more) beef cattle reach their destination with no serious problems. |

Canada is vast and has a beef cattle industry, transport system, and climate unlike other countries around the world. Canada’s recommended cattle transport practices and regulations must reflect those differences and be scientifically sound. Research that studies commercial cattle and transport trailers under typical commercial distances and conditions in Canada is the most relevant for guiding transport standards.

Driver fatigue increases the risk of livestock transport accidents. Research that documented accidents in Canada and the United States determined that 59% of accidents occurred from midnight to 9:00am and 80% of all livestock transport accidents were single-vehicle.

While there are still many transport research questions to answer, Canadian researchers have worked to:

- Establish welfare benchmarks for common industry transport practices

- Determine welfare benchmarks for compromised cattle transport

- Investigate the effects of loading density and trailer ventilation management (trailer side boards) on calf transport outcomes, welfare and health

- Examine how driver experience impacts shrink and welfare outcomes

- Determine the impact of unloading delays on welfare

- Investigate the effects of animal and handler behaviour, transport conditions, time and distance and transit, and driving practices on welfare outcomes and carcass impacts in fed cattle and market cows

- Investigate the effects of rest stop duration and quality as well as cattle type on welfare outcomes after transport

Maintaining Welfare During Transport of Cattle

Cattle may be exposed to numerous stressors before, during, and after transport. Handling during loading or unloading, being exposed to new environments such as auctions, mixing with unfamiliar cattle, or feed and water restrictions all cause stress. Other factors such as loading density, injuries or illnesses, duration of transit, and trailer environmental conditions, such as humidity, temperature, and ventilation, also affect welfare.

Handle animals with care to prevent stress

|

|

The Duffy Pattern (left) provides 12% porosity, as opposed to the 10% of porosity with the Punch Hole Pattern. The Duffy Pattern (left) provides 12% porosity, as opposed to the 10% of porosity with the Punch Hole Pattern.Photo credit: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada |

Handling and loading facilities should have solid sides, be free of broken boards or protrusions, and be well lit. Chutes should have non-slip footing, such as rubber mats, sand, gravel, or perforated concrete flooring. Loading ramps should also have traction (i.e. perpendicular cleats), be at angle of 25° or less and have no gaps between the ramps and the cattle liner. Cattle should be handled as calmly and quietly as possible during both loading and unloading to prevent bruising and other injuries related to falling or slipping.

In addition to the risk of transport injury, stress can depress the immune system. Steps taken to avoid or reduce stress in transport will reduce the risk of animals becoming sick after the trip is completed. Ensure that cattle:

- are not wet

- have the opportunity to eat and drink within five hours of loading

- have adequate bedding in trailer compartments for the duration of transit

- are loaded at an appropriate density

- have adequate ventilation during periods of time when the trucks are stationary, particularly in warm weather (> 15 °C)

Loading decisions and determining risk

Loading decisions are critical to a successful transport outcome. Producers must ensure that the animals they load are not unfit or compromised in any way. Sick or injured animals, or cattle suffering for any other reason, are not fit for transport.

Loading decisions are critical to a successful transport outcome. Producers must ensure that the animals they load are not unfit or compromised in any way. Sick or injured animals, or cattle suffering for any other reason, are not fit for transport.

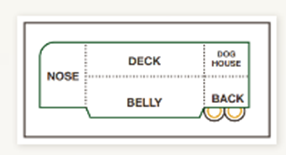

Commercial transport trailers typically contain several compartments. Cattle are sorted for each compartment according to weight and class. High risk cattle should not be placed in the doghouse, and should be the last to load and the first to unload. It is important to determine the risk level of animals and know that different classes of cattle may be at greater transport risk than others.

High Risk

|

Cows with a body condition score (BCS) of 1 should never be transported. Cows with a BCS of 2 should only be transported short distances. Learn more about how to body condition score in this video. |

Any class of animal can be a high risk to transport if the animal is sick, injured, or otherwise compromised. Market cows (i.e. cull cows) are often at the greatest risk of being compromised during transport, especially those that are older, thinner and weaker. In winter, thin haired dairy cows from an insulated barn are faced with additional challenges, particularly if they are still lactating.

When transporting market cows, pay particular attention to loading density, weather conditions and the duration in transit. Market cows should be well bedded, segregated, and when possible, loaded in the back compartment so that they are loaded last and unloaded first.

Medium Risk

Any class of cattle can be a medium risk to transport if they are exposed to stress. During the fall run, calves may be more tired and stressed due to a combination of weaning stress, commingling with calves from other herds, and unfamiliar feed in livestock markets. These calves may be at higher risk of injury in transit, and are much more likely to get sick as a result of this accumulated stress. Calves are at greater risk for poor welfare outcomes as the time in transit increases, especially around the 30 hour mark. Calves are also more sensitive than fat cattle to external temperature of less than -15 degrees or higher than 30 degrees Celsius.

Low Risk

Finished and yearling cattle are young, healthy and have good nutritional reserves, which helps them to easily withstand transport stress.

Photo credit: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Market cows are at a greater risk of becoming compromised during transport than other classes. During transport, they should never be loaded in the doghouse, they should be kept separate from other classes of cattle, and be the last to load and the first to unload. |

Use a Responsible Livestock Transport Company

Transporting live loads of cattle is much different than static freight. Responsible livestock haulers play an important role in making sure animals reach their destination safely.

Drivers should:

- avoid rapid acceleration

- avoid any sudden stops or sharp corners

- stop periodically to check that the cattle are safe (i.e. no animals have gone down)

- adhere to appropriate feed, water and rest intervals

- maintain communications with receiver before and following arrival to help manage any challenges

- have a plan to deal with inclement weather, vehicle malfunctions, road construction, or any delays that increase the time animals are on the truck

- be familiar with cattle behaviour and follow optimal handling practices while loading and unloading cattle

Facility Design and Transport Procedures to Prevent Carcass Bruising

Carcass bruising costs the industry an estimated $1.90/head. To minimize bruising from transport, cattle must be handled carefully using well-designed facilities, and loaded on trailers with proper footing at appropriate densities.

Handling during loading and unloading can be more stressful that transport itself. Improper animal handling has a negative effect on meat quality and also has negative welfare implications and potentially reduces consumer confidence.

Facilities can be designed or modified to improve handling:

- Incorporate chutes with solid sides to keep the animals focused on moving ahead

- Curved chutes promote flow by taking advantage of an animal’s tendency to walk in a circular manner

- Provide non-slip footing by placing grooves in concrete floors, using metal grids, applying sand or dirt to the area, or using rubber matting

- Maintain facilities, replace broken or protruding boards, panels, nails, bolts, or other metal hazards

- Ensure handling area is well lit with non-direct lighting that doesn’t shine in the animal’s face

- Loading docks or ramps should not have any gaps between the ramp and the cattle liner

- Ramp should not be at an angle steeper than 20-25°

- Ensure the loading ramp has perpendicular cleats at regular intervals to provide proper footing

Low-stress cattle handling is the practice of moving cattle calmly and slowly, with infrequent, or no use of electric prodding. Low-stress handling includes reduced noise, refraining from shouting, handling cattle in small groups as opposed to individually and avoiding use of unfamiliar animals or untrained dogs.

The Future of Cattle Transport

Canadian scientists are currently undertaking a study on the effects of varied rest stop conditions during long-haul transit. In one experiment, the effect of the duration of transit and the length of the rest stop (4, 8, or 12 hours) will be analysed. In a concurrent study, researchers will examine the source of calves (i.e. auction mart or ranch direct) and the duration of rest the animals receive and their resulting health and behaviour. In another treatment, a portion of the load will experience a high quality rest area with ample room, proper bedding, access to adequate quality feed and water while the other portion is provided low quality rest. The impact of the quality of rest will be evaluated. Canadian researchers are also continuing to study other aspects of transport welfare including:

- Risk factors associated with compromised welfare

- Loading densities

- Unloading delays and associated trailer conditions impacting cattle and carcass bruising

- Arrival conditions

- Bedding use

- Ride quality (i.e. types of movement) and effect on bruising

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info [at] beefresearch [dot] ca.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Karen Schwartzkopf-Genswein, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Researcher focused on animal welfare standards and reducing transport stress in farm animals for contributing her time and expertise to writing this page.

This topic was last revised on February 25, 2022 at 12:10 PM.

View Web Page

View Web Page View PDF

View PDF