Impact of Oil & Natural Gas Production

Raising livestock adjacent to oil and gas production facilities is a reality for cattle producers in many parts of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and northern British Columbia. These herds can be exposed to emissions due to routine production activities and accidental releases of volatile products such as H2S, SO2 and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). It is also possible for cattle to be exposed to liquid products such as crude oil, drilling mud, frac fluid, high salt produced water, and a variety of products used to assist in production or movement through gathering systems.

On this page:

Concerns

|

Concerns from the livestock industry and suggestions for research to address potential impacts were identified and documented during the 1980s and 1990s. Multi-stakeholder consultations included workshops and symposia on the effects of emissions (Edmonton, May and November 1986; Red Deer, April 1996), a scientists’ advisory meeting (Edmonton, January 1997), and a conference on the issue of flaring in the petroleum industry (Calgary, April 1999). |

Photo credit: Western Canada Beef Productivity Study Photo credit: Western Canada Beef Productivity Study |

At the Red Deer symposium, participants raised several questions including whether animal health was affected by acid-forming emissions, and whether there were effects of exposure on the respiratory, immunological, and reproductive systems. Participants also identified a need to investigate the potential effects of chronic exposure.

In July 1996, the Alberta Environmental Centre released a report prepared for the Alberta Cattle Commission on “Cattle and the Oil and Gas Industry in Alberta: A Literature Review with Recommendations for Environmental Management.” The report similarly recommended studying the “possible toxicological effects on cattle from prolonged, low-level exposure to contaminants… with special attention to the reproductive and immunological systems” (AEC, 1996).

Early Research Findings

Two observational studies were done during this period. One study drew on historical survey and modeled exposure data (Scott et al., 2003 a,b). The other was an intensive, multiyear, on-farm study of herds in west-central Alberta (Waldner et al., 2001a,b). The authors suggested that there might be an association between emissions from sour gas processing facilities and some reproductive outcomes in cattle.

In one study, flaring at oil and gas battery sites was associated with an increased risk of stillbirths in cow-calf herds (Waldner et al., 2001a). In the other study, Scott et al. (2003a) reported that peak monthly levels of exposure to gas plant emissions, estimated by dispersion models, were associated with increased age at first calving in dairy heifers. Scott et al. (2003b) also found a weak association between increased calving interval and the highest estimated levels of exposure.

The Western Canada Beef Productivity Study

In response to these questions, more than 200 ranchers were recruited and their 33,000 beef cows were followed from the beginning of the breeding season in 2001 through pregnancy testing in 2002 (Waldner, 2008a).

Objective

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether beef cattle exposed to emissions from the oil and gas industry were at greater risk of reproductive failure and calf death than those less exposed.

Methods

| Sulfur dioxide (SO2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) were measured using passive air monitors installed at each pasture and the results were compared to the performance of individual animals (Waldner, 2008b). The density of oil and gas well sites surrounding each pasture was used as an additional measure of exposure (Waldner, 2008c). |  Photo credit: Western Canada Beef Productivity Study Photo credit: Western Canada Beef Productivity Study |

Results

In this study, there was no association between any measure of exposure to the oil and gas industry and the occurrence of non-pregnancy (Waldner, 2008d), abortion, or stillbirth (Waldner, 2009). The time from breeding to calving was 3.0 days longer for mature cows exposed to VOCs measured as benzene concentrations in the highest 25% compared with cows exposed to benzene concentrations in the lowest 25% (Waldner, 2008d).

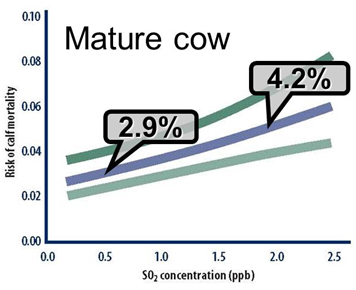

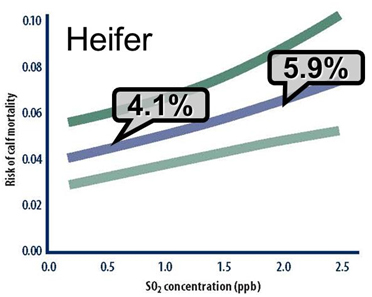

Exposure to SO2 near the time of calving was associated with an increase in calf death losses (Waldner, 2008e). For every 1 ppb increase in SO2 in the 3-month period before calving, the odds of calf mortality increased by 1.3 times. This was the equivalent to a 1 to 2% increase in total calf mortality before 3 months of age associated with exposure to the highest measured concentrations of SO2 (Figure 1 and 2). For the average ranch in this study (approximately 150 cows), this would be equivalent to the loss of 2 to 3 additional calves.

Figure 1. This figure depicts the observed association between SO2 exposure and calf loss. Here we see the predicted death loss for male calves born to mature cows at 0oC in March across the range of SO2 concentrations recording during the study. Cow age, calf sex, temperature on the day the calf was born, and month of calving were also identified as important predictors of calf survival.

Figure 2. This second figure depicts the predicted death loss for male calves born to heifers at 0oC in March across the range of SO2 concentrations observed during the study. Note the average expected death loss is higher for heifers than for the mature cows in Figure 1.

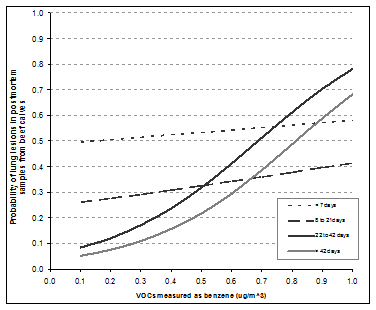

Increasing postnatal airborne exposures to volatile organic compounds (VOCs) measured as benzene and toluene were associated with increased frequency of lung lesions, including pneumonia, found in calves that died during the study (Waldner and Clark, 2009). The association between VOCs measured as benzene and respiratory lesions was most apparent in calves older than 3 weeks (Figure 3).

Increasing exposure to SO2 during gestation was also associated with more frequent changes in the skeletal and heart muscle observed in the calves that died during the study.

Figure 3. This figure describes the frequency of microscopic lung changes, including pneumonia, in calves of different ages that died during the study and were examined post mortem by the herd veterinarian. Note lung lesions were most common in calves that died after 3 weeks of age and were exposed to VOCs measured as the highest observed concentrations of benzene.

The immune system in these animals was evaluated using a series of measurements on blood and tissues. T-lymphocytes were found to be lower in calves exposed to the highest levels of benzene and toluene, which may make the animals less able to respond to infection. Numbers of two specific types of circulating T-lymphocytes were 42% and 43% lower, respectively, in calves exposed to the highest 25% of VOCs measured as airborne concentrations of benzene compared with calves exposed to concentrations in the lowest 25% (Bechtel et al., 2009b). A decrease in one type of T-cells in calves was also seen at the highest concentrations of toluene. Similarly, a 30% decrease in one type of T-lymphocytes was seen in yearling heifers exposed to the highest 25% concentrations of toluene (Bechtel et al., 2009c).

Air Quality Guidelines

The World Health Organization (WHO) has examined similar human health questions. In a review and meta-analyses of approximately 200 peer-reviewed scientific reports the WHO developed guidelines for critical air pollutants (WHO, 2006). The WHO has established a 24-hour average maximum SO2 guideline of 20 µg/m3 (~7.7 ppb). The WHO also identified studies where increased mortality was associated with average SO2 concentrations as low as 5 µg/m3 (~1.9 ppb), which was within the concentrations reported in the cattle study described above.

Progress on Emissions Reduction

Alberta has made considerable progress in reducing emissions from routine production activities (EUB ST60B, 2007). The Alberta Ambient Air Quality Objectives and Guidelines value for 24 hour average SO2 concentration were 125 µg/m3 (~48 ppb) (Alberta Environment, 2011) at the time this report was prepared.

Suspect a Problem in Your Herd?

Consult your veterinarian as soon as you suspect you might have a problem. Request that objective data and tissue samples are collected and preserved until the matter is resolved. Your veterinarian can help you document the exposure and current health of your herd.

| Documentation is critical to examining livestock health problems that could potentially be associated with exposure to oil and gas industry emissions. Detailed records of herd management and both historical and current production have been very useful in successful investigations. |

|

These records need to be adequately detailed and accurate to demonstrate:

- a sufficient period before exposure,

- any substantial changes in:

- production,

- feed consumption,

- sickness or

- treatments.

- the role of adequate

- nutrition,

- parasite control,

- vaccination,

- breeding soundness evaluations of bulls,

- routine herd management activities

- any changes in herd health and performance.

The diagnosis of any adverse health and production effects of exposure to emissions from oil or gas production facilities often depends on elimination of all other possible causes. Therefore, extensive testing is often necessary to rule out other conditions (e.g. BVDV, other infectious diseases, nutritional deficiencies) and to document whether sufficient exposure occurred to potentially result in harm.

In many cases, the toxic compound may have dispersed from the air or animal tissues before diagnostic tests can be performed. Diagnostic tests are very expensive. As a result, it is very difficult to conclusively prove that oil and gas activity was responsible for a particular case of animal sickness or mortality. The producer must clearly demonstrate that herd management was not responsible for the observed changes.

In the case of accidental exposure to solids or liquids, both environmental and tissue samples can be collected to confirm exposure and analytically link the contaminant in the environment to any ingested by the animal.This requires careful coordination with a qualified laboratory to ensure the results of any testing will be meaningful.

In the case of exposure to gases, such as H2S or SO2, environmental samples and animals tissues are less likely to be available or appropriate for documenting exposure. This increases the importance of objectively ruling out other potential causes.

Feedback

Feedback and questions on the content of this page are welcome. Please e-mail us at info [at] beefresearch [dot] ca.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to:

- Cheryl Waldner DVM PhD, Professor of Epidemiology, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, and Professor, School of Public Health, University of Saskatchewan

- Richard Kennedy DVM PhD, epidemiological researcher and Associate Editor for the Canadian Veterinary Journal

for contributing their time and expertise to writing this page.

This topic was last revised on February 29, 2016 at 9:02 AM.

View Web Page

View Web Page View PDF

View PDF